“Preserving the culture and history of Kurdistan is a sacred act,” Pishtiwan said, leafing through volumes and manuscripts from the public library in the city of Dohuk in the autonomous Kurdistan region of northern Iraq.

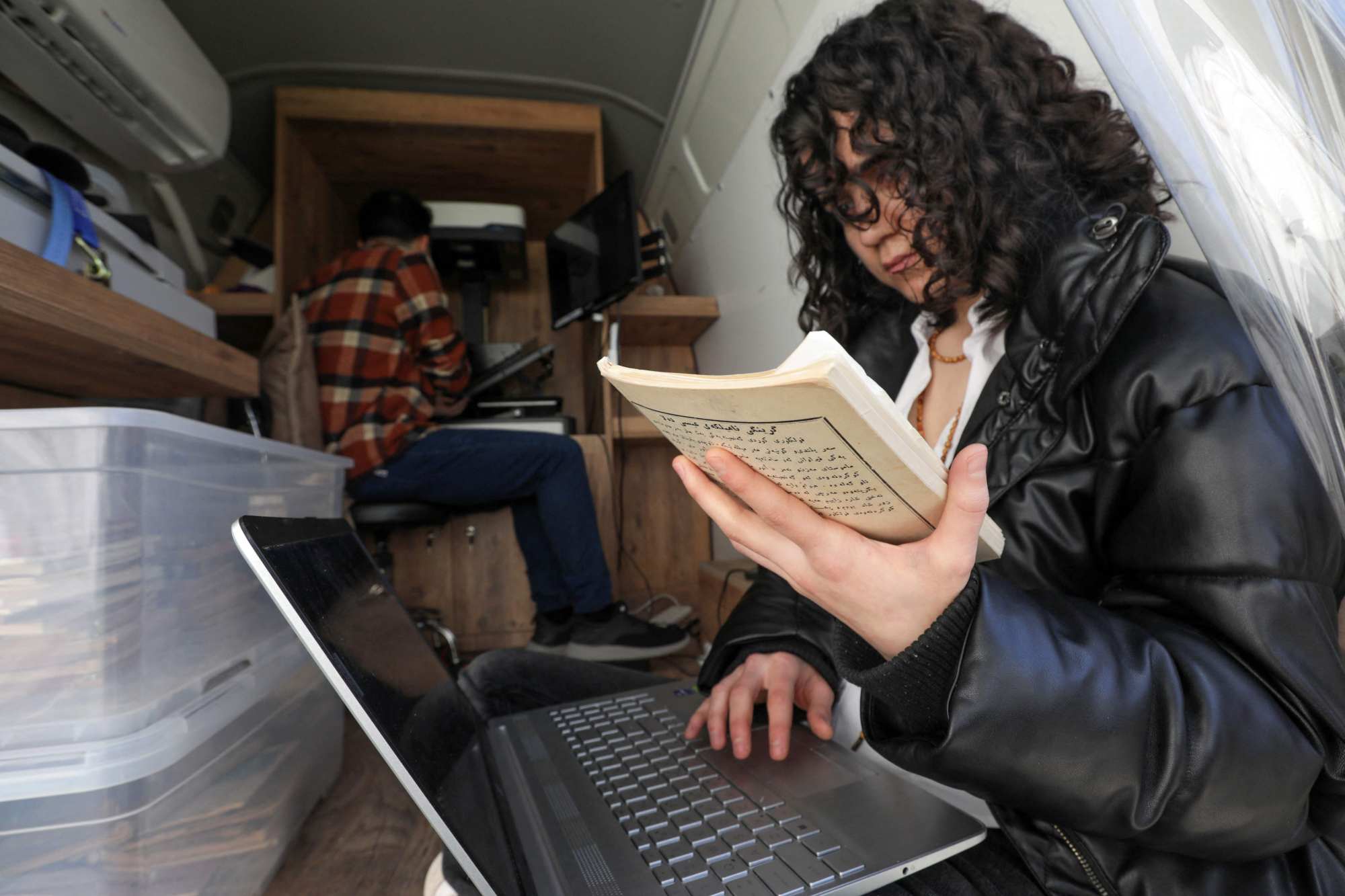

“We aim to digitize old, rare and weak books, so they don’t disappear,” the 23-year-old added, holding a Kurdish teacher’s torn diaries published in 1960.

In Iraq, the Kurdish language was mostly marginalized until the autonomous Kurdish region in the north gained greater freedom after the defeat of Saddam Hussein in the 1990-1991 Gulf War.

After the 2003 US-led invasion toppled the dictator, the remaining documents were scattered among libraries and universities or kept in private collections.

Pishtiwan and his colleagues travel once a week in their small white truck from the regional capital, Erbil, to other Kurdish towns and cities to find “rare and old” books.

They are looking for texts that provide insight into Kurdish life, which spans centuries and dialects.

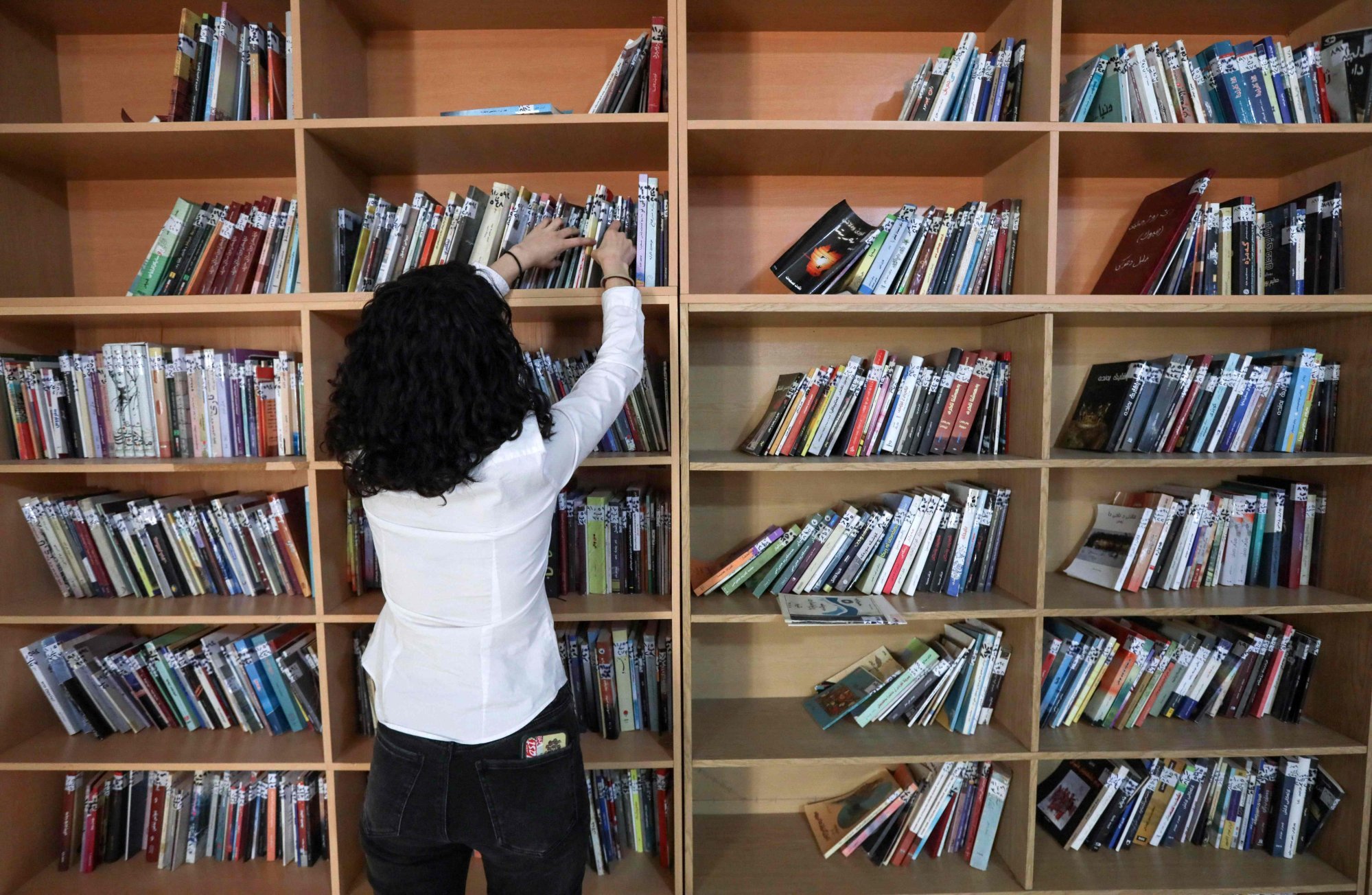

At the Dohuk Library, an archiving team scans wooden bookshelves in search of hidden gems.

With the help of the library director, they carefully collect a diverse collection of more than 35 books on poetry, politics, language and history, written in several Kurdish dialects and some in Arabic.

Peshtivan holds up a book of ancient Kurdish folktales named after the 16th-century Kurdish princess Zanzade, before gently turning the fragile pages of another religious tome, tracing the line with his fingers.

Back in the truck, equipped with two devices connected to a screen, the small team begins the hours-long scanning process before returning the books to the library.

In the absence of an online archive, the Kurdistan Center for Arts and Culture, a non-profit organization founded by the nephew of the region's president, Nechirvan Barzani, launched a digitization project in July.

They hope to make the texts available to the public for free on KCAC's new website in April.

This archive will belong to all Kurds to use and to help enhance our understanding of ourselves

More than 950 items have been archived so far, including a collection of manuscripts from the Kurdish Baban Emirate in today's Sulaymaniyah region dating back to the 19th century.

“The goal is to provide primary sources for Kurdish readers and researchers,” said Mehmet Fatih, Executive Director of KCAC. “This archive will belong to all Kurds to use and to help enhance our understanding of ourselves.”

Dohuk Library Director, Masoud Khalid, provided the KCAC team with access to manuscripts and documents gathering dust on its shelves, but the team was unable to obtain permission from the owners of some documents to convert them to digital form immediately.

Khaled said: “We have books that were printed a long time ago, whose owners or authors died, and the publishing houses will not reprint them.”

The 55-year-old added that the digitization of the collection means that “if we want to open an electronic library, our books will be ready.”

Hana Kaki Hiran, imam of a mosque in the city of Hiran, uncovered a treasure for the KCAC team – several generations-old manuscripts from a religious school founded in the 18th century.

Hiran said that since its founding, the school had collected manuscripts, but many of them were destroyed during the first war between the Kurds and the Iraqi state between 1961 and 1970.

“Only 20 manuscripts remain today,” including centuries-old poems, the imam said.

He is now waiting for the KCAC website to launch in April to refer people to view manuscripts.

“It's time to get it out there and make it available to everyone.”