Wildcards abound, making it impossible to provide very specific predictions. Details will become clearer by Wednesday and especially Thursday, when it may be possible to start predicting when rain will start and stop in specific locations, who will see rain versus snow, and how much will fall.

However, some of the country's most populous cities may be in for accumulating snow or a combination of snow, sleet and rain.

Here we outline some plausible scenarios, what we're seeing, and what the impacts might be.

At present, a “shortwave”, or pocket of cold, high-altitude, low-pressure, circulating air, exists south of the Aleutian Islands in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. This system will dive to the southeast over the Lower 48 in the coming days, dumping rain over the Southern Plains and Deep South on Friday, then generating an area of low pressure near the mid-Atlantic coast over the weekend.

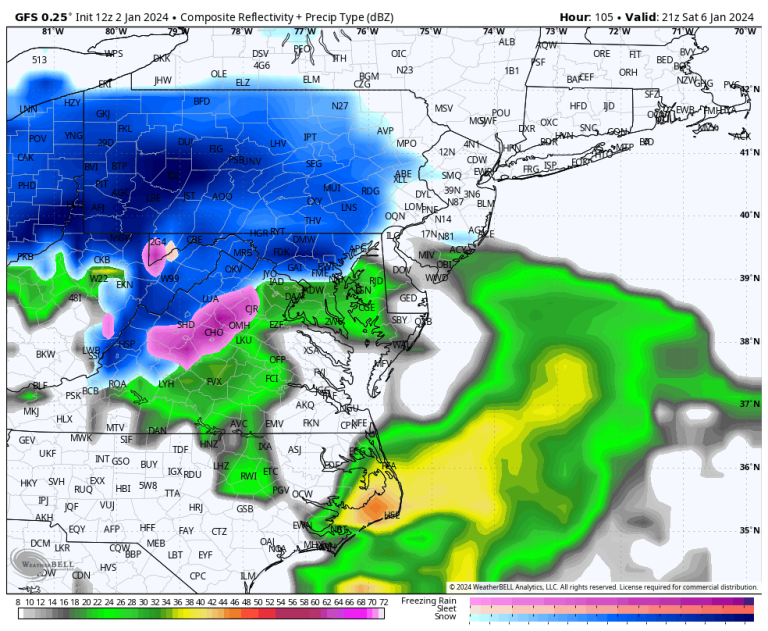

This low pressure system will travel north along the East Coast. To the east, offshore, a tongue of warm, moist air will curl north, fanning thunderstorms over the Gulf Stream. Some of this moisture will move back to the west and northwest around the low pressure center, falling as snow on the cold side of the storm. That will be at least 50 to 100 miles west of the storm's track.

How far the low pressure system tracks near or far from the coast will have major impacts on snowfall. Tracking low pressure along the coast or inland will draw enough warm air west for more rain along the I-95 corridor, with heavy snow falling mostly in the mountains. But if the low's path is slightly offshore, it could allow enough cold air to remain in place for the first significant snowfall in two years in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York.

The worst of the storm will come Saturday into Sunday. For the Piedmont in western North Carolina, it will start before dawn Saturday. Then between early morning and early afternoon, it will expand across the mid-Atlantic, reaching the northeast on Saturday evening.

Since the I-95 corridor from Washington to New York can straddle the rain and snow line, likely scenarios mostly include precipitation, mostly snow or a messy mix of rain. For this reason, it is impossible to predict specific snow totals in advance.

Providence, Rhode Island; Boston; Portland, Maine has better snowfall chances than I-95 cities to the south.

Heavy snowfall, possibly exceeding one foot, is likely in the Appalachians, where confidence in the forecast is highest.

Models unusually agree that a low pressure system will form somewhere near the mid-Atlantic coast on Saturday. With enough moisture, it stands to reason that significant amounts of rain, snow, or both could accumulate in an area stretching from Virginia to Maine.

We know that the air leading up to the storm won't be particularly cold, which means it won't be a severe blizzard. What is more likely is snow falling inland, especially at higher elevations where it is colder.

What bothers forecasters is that predicting the types of rain that will fall on major cities is highly uncertain, especially from Washington to New York.

The original upper air disturbance, still offshore, has not yet moved over the Pacific Northwest. Once that is done, the National Weather Service will be able to launch weather balloons into it. This way, important data about its shape, strength and movement will be ascertained, which will be fed into computer models to better simulate the upcoming storm.

We don't know exactly where the storm will follow, so we can't predict where the line of rain and snow will be. That means anyone predicting specific rain or snow totals in the large population centers along I-95 is basically guessing.

We also don't know how strong the “50-50 low” will be — or the low pressure area near 50 degrees north latitude and 50 degrees west longitude near Newfoundland. This low is responsible for the cold air swirling southward ahead of the storm, coinciding with the high pressure area in southeastern Canada. Models don't expect this pair of compression systems to become particularly strong, limiting the amount of cold air. For this reason, snow totals may not be as large east of the mountains in the mid-Atlantic.

We also don't know where the western edge of the precipitation shield will be created. In such storms, the western edge is usually very sharp. It's still unclear exactly where the heavy snowfall in northern and western New England will stop.

Taking it all together, it's too early to know exactly what will happen with this storm.

For many, this is the first massive chance of snow in the past two years, after successive lackluster winters.

We will continue to share updates and adjust the latest forecasts.