Alexei Navalny is mourned as Russia's most outspoken, sophisticated and Westernized politician. Yet Navalny's political struggle against tyranny, which ended in an Arctic penal colony in what appears to be a state-sponsored murder, makes his “life and fate” very Russian – part of a tradition of moral defiance against cruel and deceptive tyranny.

A fateful opponent

Navalny could have been a successful politician in a democratic country. But he was a political opponent in Putin's Russia, which has evolved from a corrupt authoritarian state into a thuggish and brutal dictatorship. One cannot pursue a political career in present-day Russia: you can either be a loyal servant of the Kremlin or a part of the always silent politics. the people (general public). Any sign of disloyalty or dissent is suppressed. Navalny knew this better than anyone: in 2020, he was poisoned with a nerve agent by Putin's secret police. However, he returned to Moscow from Germany after treatment that saved his life, knowing full well that he would be immediately arrested and put behind bars.

What could explain this seemingly irrational move? Navalny's return to Moscow – on that fateful day – marked the real beginning of his journey Russian story. The history of the Russian intelligentsia, Russian literature, the tradition of political dissent and truth-telling, and the quasi-religious pursuit of a virtuous life are elements of its plot.

Russian writer Dmitry Glukhovsky observes that Navalny, a true man of flesh and blood, warts and all — full of all sorts of contradictions given his flirtation with Russian ethno-nationalism — has been transformed into “a flawless hero, part of a religious myth.” Glukhovsky adds that his actions, courage, and moral choices are seen as symbolizing “the life of a saint.” “The death of a martyr.”

Strict ethical standards

The Russian intelligentsia, which emerged as a social group in the 1830s, sought moral perfection. Their powerful aspirations were born of two close intellectual traditions: one religious, stemming from Eastern (Byzantine) Christianity; the other, a secular legacy of Enlightenment ethics. Concept The most amazing (Conscience) was at the heart of the soul of the first Russian intelligentsia. Having a “clear conscience”—living unhesitatingly according to principles of truth—served as a deeply rooted social ideal for intellectuals.

Historically, the Russian intelligentsia arose from the confrontation with tsarist autocracy. Opposition to the bureaucratic establishment shaped intellectuals' codes of behavior and their beliefs about what is right and what is wrong. As Russian cultural historian Boris Ouspensky wrote: “It is precisely the division between the intelligentsia and the tsar that lies at the origins of the Russian intelligentsia.” Russian tasty They are always in opposition, as their moral values contradict the workings of the oppressive state system.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, intellectuals may have left the historical scene. However, their moral principles did not disappear: many Russians absorbed the ideals of the intelligentsia by reading classical Russian literature, which in turn was a product of the creative efforts of the Russian intelligentsia. Unlike medieval Old Russian literature, which was completely religious in nature, the great Russian novel of the 19th and early 20th centuries performs an educational function: it explains the life of dignity, the endless struggle between good and evil, the choice between right and wrong. In numerous memoirs and interviews, prominent members of the Soviet dissident movement asserted that the subversive, “quasi-religious” essence of Russian literature shaped their moral principles and negative attitude toward the “immoral” Soviet regime.

The rule of the martyr

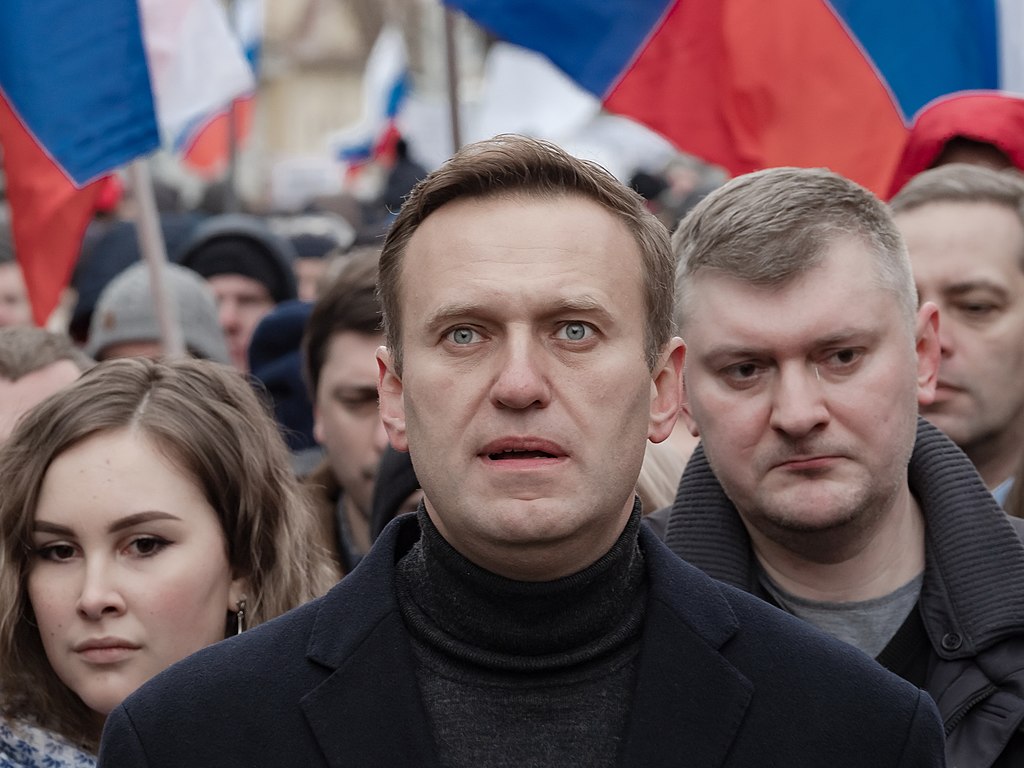

Alexei Navalny, 2020. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Alexei Navalny, born in 1976, belonged to Russia's new generation: he was a teenager when communism fell and the Soviet Union disintegrated. However, the factors that shaped his moral outlook appear to be the same as those that had been influential during previous decades. Russian literature seems to have played an important role. In a letter he sent to Russian opposition journalist Sergei Parkhomenko shortly before his death, Navalny discussed some Russian classics. He focused on Chekhov's stories and compared the dark realism of some pieces to the works of Dostoyevsky. The letter ended with a telling exhortation: “One should read the classics.” We don't know them well enough. It is also difficult to avoid the direct parallel between Navalny's passionate desire for the truth and Russia's dissident literary tradition of truth-telling, best embodied in Alexander Solzhenitsyn's 1974 essay. Living is not by lies; All Navalny's live broadcasts always end with the phrase: “Subscribe to our channel: here we tell the truth.”

Alexei Navalny's moral integrity, personal courage, and courageous determination to stand by his principles, whatever the circumstances, put him on par with a long line of Russian victims of political repression, who have challenged the Russian juggernaut over the past two centuries. Now Russia's divided opposition has a powerful hero myth and symbol to rally around. Putin (or “Fortified Grandpa,” as Navalny used to sarcastically call him) was afraid of his most prominent political opponents when he was alive. Now that Navalny has died, Putin arguably finds himself in an even worse position. The Kremlin tyrant should be reminded of Søren Kierkegaard's famous quote: “The tyrant dies and his rule ends; The martyr dies and his rule begins.