Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found important clues about how people make choices that involve obtaining information about the future. Scientists have identified a set of mental rules that govern decision-making about rewards, including cognitive rewards such as satisfying curiosity, and they have also identified the part of the brain that regulates this type of decision-making.

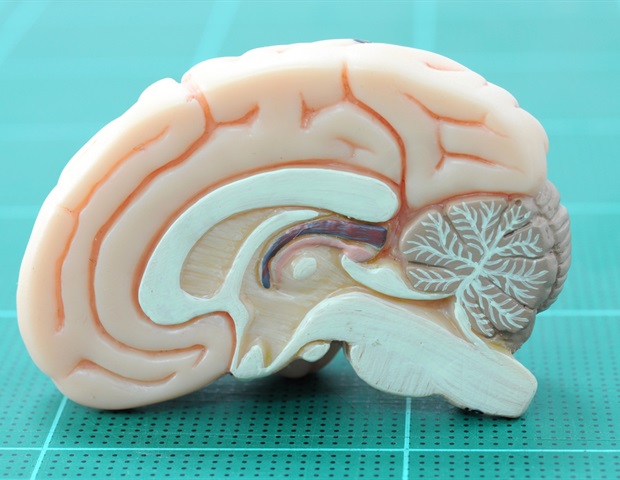

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have new insight into what goes on inside people's heads as they make decisions to gain information about the future. Scientists have identified a set of mental rules that govern decision-making about physical rewards – for example, food or money – and cognitive rewards – such as the joy we feel when accessing desired information. They identified the part of the brain that regulates this type of decision making. This process occurs in the lateral habenula, an ancient brain structure shared by distantly related species such as humans and fish.

Not only do the findings provide insight into the body's most mysterious organ, they have the potential to help people struggling with difficult choices, whether it's because of the inherent complexity of some decisions — such as whether to take a genetic test that might reveal unwelcome information — Or due to psychological illnesses that affect the ability to make decisions, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, and depression.

The study is available in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Identifying the circuits involved in assigning value to cognitive rewards, such as information about the future, is really important, because this type of evaluation is often broken down in mental disorders. If we can understand exactly which part of an individual's decision-making process is dysfunctional, we may be able to precisely target this aspect of the process and treat some mental illnesses more effectively.

Ilya Monosov, Ph.D., senior author, is professor of neuroscience at the University of Washington

Choosing between two options often requires evaluating the values of multiple factors and making trade-offs between them. Some of these factors are tangible and practical. But there are also intangible factors that can provide a strong motivation to choose one option over another, such as the desire to satisfy curiosity and obtain information. Some information has practical value, of course, such as advance warning of an upcoming hurricane. But experiments have shown that humans and animals value information even when they cannot exploit it for anything useful.

“Take for example a student who takes a final exam and then wants to know the results immediately,” said co-first author Yang Yangfeng, an MD/PhD student who designed and led the study experiments with human participants. . “Finding out your result today versus finding out in a week won't change the results or give you any kind of advantage. But some people want to know so badly that they'll pay to find out early. This is called rummaging and trying to obtain information for its own sake.”

Historically, the drive to obtain practical rewards, such as money or food, and the drive to obtain information have been studied as two separate phenomena. The researchers said this division is artificial and oversimplifies the choices people make in the real world.

Feng and co-first author Ethan Bromberg-Martin, Ph.D., a senior scientist in the Monosov lab, designed experiments that required participants to make trade-offs between rewards and non-instrumental information to reach a final decision. Study participants were given a choice between two options, each of which gave them a chance to get a few cents. The amount of money they can win and the probability of winning varies. Some options came with the promise of knowing the outcome early, before the actual money arrived. In separate experiments, the monkeys were presented with similar options, where juice was the reward instead of money.

“By analyzing the trade-offs that individuals make, we were able to establish some of the rules that individuals use to decide how much they are willing to pay for information,” Bromberg-Martin said. “These rules generalize between humans and animals, suggesting that this abstract value may be conserved through evolution.”

One of the key principles they uncover is that individuals search for information largely to solve the problem of uncertainty. The greater the uncertainty, the more they are willing to pay for information about it. Intuitively, this makes sense. You'll likely be willing to pay more to know the outcome of a $100 bet than you would for a $1 bet, especially if you can get the information sooner rather than later. These principles and others form a logical framework upon which the brain relies to make choices.

But sometimes the system crashes.

“Some people with OCD exhibit what are known as checking behaviors, where they go back and check the same thing over and over again,” Monosov said. “This is anomalous information-seeking behavior, mainly due to poor handling of uncertainty.”

As part of this study, the team discovered that decision-making algorithms are implemented through a neural circuit that culminates in the lateral habenula, a small structure located deep in the brain. Lateral release is a master regulator of dopamine and has been linked to mental illnesses including depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The team is working on using tasks that require participants to make choices, similar to those in this study, to classify people with OCD into subtypes that correspond to how their brains process uncertainty. Doing so would be a step toward more targeted treatments.

“A person may be OK in some ways, but their uncertainty processing is broken in one specific way,” Monosov said. “Instead of saying someone has a broad mental disorder like OCD, we can say their uncertainty processing is broken in this specific way, and here's how to modify it. It's a step toward more personalized medicine for mental illness.”

source:

Washington University School of Medicine

Magazine reference:

Bromberg Martin, E.S., et al. (2024). A neural mechanism for preserved value computations that integrates information and rewards. Natural Neuroscience. doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01511-4.