It is difficult to follow recent events in Israel – the latest wave of successive violence in a war that has lasted for more than seven decades, sometimes raging, sometimes burning, and always present – without a sense of growing despair.

At the time of writing, the IDF is on the verge of invading northern Gaza, the fault lines of the underlying conflict are cracking across the region, and the thousands already dead appear to be only a prelude to an even greater tragedy.

The case for de-escalation is frustratingly simple. Escalation is an essential feature of any war, but it should not be taken as a determining factor that strictly determines a causal chain of events. Violence has no intrinsic logic, and dictates no necessity; This means that any escalation of violence, as Carl von Clausewitz argued, is at its root a political issue. We enter wars for political reasons, and we only solve them through political means.

Wars become longer and more destructive, more foolish and debilitating, and the more distorted the political situation becomes – stifling potential alternatives to simply prolonging the violence and thus giving war the illusory air of necessity.

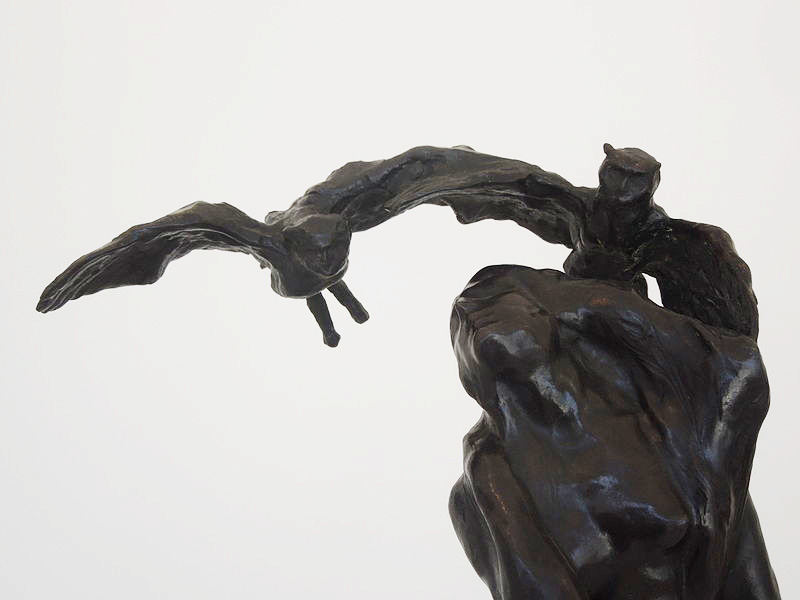

Bohumil Kafka, “The Sleepwalker”, 1906, National Museum in Prague. Source: Wikimedia Commons

I believe this is the situation in Palestine: the protracted impasse in the two-state solution, coupled with internal divisions that have gradually weakened the political system of both Palestinians and Israelis, has led to a situation in which extremists are increasingly prevailing, taking these two ancient peoples onto a path of war. Endless.

Again, this is not due to any intrinsic logic to the violence, but merely to the dynamics of an increasingly deteriorating political situation. When Anwar Sadat was assassinated in 1981, peace with Egypt held, indicating the political flexibility of moderates that had been in increasing decline since the shooting death of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, and now appears to have been completely eliminated.

None of this argues decisively against the simple argument for de-escalation: fundamentally changing the political dynamic by refusing to escalate violence, and using that refusal as a starting point for creating the conditions necessary to extinguish the influence of extremism. Once again, moderate heads are victorious, seeking a lasting peace based on basic principles of human dignity, and refusing to grant terrorists any political veto power.

There is no decisive political argument – and it is certainly not a half-decent one army Argument – that the only way to respond to the slaughter of civilians is to engage in urban combat with a limited group of militants who are quite willing to use the very people they are supposedly fighting for as human shields. This is as absurd as the assumption that the only meaningful way to address the suffering of the Palestinian people is to massacre Israeli citizens. The political situation in the aftermath of either action does not fundamentally change, the war will continue forever, and the only benefits one can hope to reap are the empty gratification of revenge – a gratification that I have always found morally repugnant.

Yet what is simple and obvious is often the first victim of the distorting politics of war, with its devastating mobilization of hatred.

My greatest fear – not just for Israel and Palestine, but also for many other parts of the world where political responsibility is undermined by drugs of anger and resentment – is that our political life is currently locked in a downward spiral by the choices it can afford. It seems more and more restricted, more and more tied to the irresolution of permanent conflict.

We are proving once again that we are oblivious to violence, despite all the legacies of history in which we have repeatedly walked towards mass disaster.

October 18, 2023