I'd be lying if I said the war destroyed my habits. It is also tempting to say that everything changed overnight, when a shy art researcher turned into a brave war journalist. But before that it was my father's asthma, my grandmother's dementia, my uncle's deteriorating eyesight, or, for that matter, a cockroach that snuck through an air vent. But if you really want to come to terms with everything that happened, you have to start at the beginning.

When you are born into a family whose relatives were in concentration camps, it inevitably has certain repercussions. In a way, it determines one's future from childhood, right down to the special types of spasms, visceral speech, and chronic diseases that one develops. Looking back, my modest history of self-actualization, in which I came to certain conclusions (and ignored others), was largely predictable. Could I have understood this beforehand?

My love affair with writing began with a teenager's escape from his daily surroundings. The lush daily life in Ukraine, which has probably swallowed up more riots, unrest, free fall and mutilation than could have been contained in any other European country in the past 30 years, is (somehow) quite idyllic. However, I saw it as a dreary, soulless state of nature that wasn't much to brag about, let alone question. Writing essays and other texts became an easy way to turn into a more meaning-laden scenography, such as the Dionysian world, or One Thousand and One Nights, or Shakespeare's Globe Theater – in short, things I had never seen before and places I had never been. And for this very explicit but unsubstantiated reason, I felt as if nothing else mattered, as if these things and places trumped all the purges, imprisonments, and hostilities with which those closest to my family were littered.

Maybe it was my father's incomprehensible mumbling that made me taciturn, not the other way around. He was a seventy-three-year-old Soviet engineer who was fond of physics and mathematics and would like to believe that all knowledge worthy of the name could be illustrated by numbers and tables, but over time he became strangely ignorant of its validity. When the Soviet Union collapsed, he was invited to move to the United States, but he remained in his room in an old factory without heating, wrapping his computer in his old jacket, until all factory operations ceased to function. This decision was often described as “righteous” and “straightforward” (wasn’t that exactly the reason I justified my stay in Ukraine?), when in fact this choice may have been the direct cause that ultimately led to his severe asthma. The strong medications that you have to take in such cases lead in the long run to kidney disease that can lead to this

Contributing to the confusion of one's consciousness. And in that particular case, I, an insecure writer,

I found him in bed a few years ago.

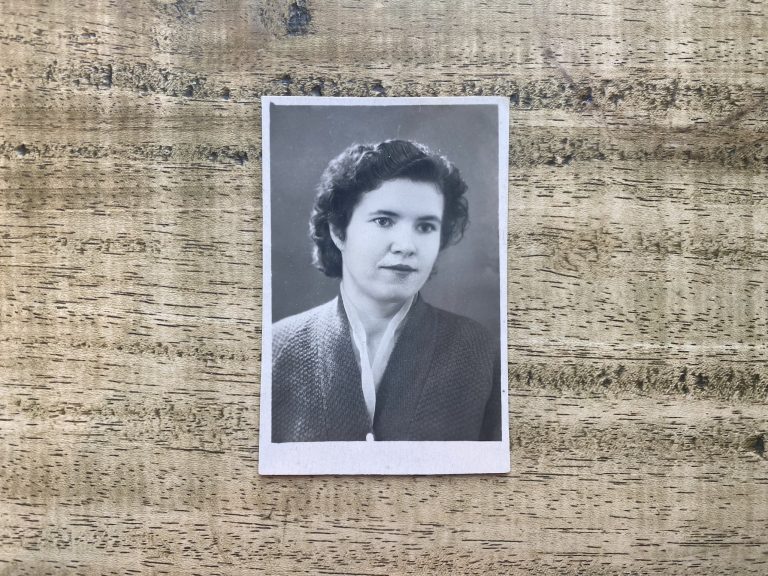

While he was being punished for his bad habits – which were not as righteous as they may seem – my grandmother was slowly dying. We managed to get her out of Nikopol – a Ukrainian city that was often bombed – almost two years before the war, and when she was forcibly taken out of her dreary and very dear routine, she would wander through the rooms and could not remember our names but she told over and over with emotion about a giant insect crawling up my face. Her mother when she died in a railway carriage on her way to Nazi Germany. I heard that story at least once a year, when every summer I was sent to my grandmother's cabin, but it was not until I became an adult that the true meaning was revealed to me. Partly because children have a knack for seeing all scary tales as evening entertainment, and partly because she likes to have them mixed in with all the burglar stories she always tells, for example a story about how she herself, as a beautiful curvy young woman, used to run cold water From the balcony to his unfortunate fans.

Of course, she eventually married one of those fans, because her family died in World War II and she needed food on the table. Out of this sad alliance came my uncle, whom she never loved, even though he was the only child who never left home. When he was five years old, he contracted polio and was subjected to abuse, which left him with a limp and poor eyesight, and was constantly scolded for almost everything by his mother, who would have preferred him to be less like her husband. So he became depressed, was never able to get a girlfriend and kept up with my grandmother in a somewhat Freudian way. He also came into our little family nest, into my mother (who was lucky enough to be loved and educated), because he was essentially a helpless extension of my grandmother and had no one to hold on to.

–

A person's youth can end in many ways, and so did mine. Conditions that I saw as banal, unimportant, and imaginary closed the door of my Soviet-like room and created the order that was to prevail when I was just over twenty years old, that is, the last thing on my mind was to do something cultural.

When answers to medical tests become one's main literature, one discovers a wealth of facts that no one ever knew in the world of symbols. One quickly learns that the excrement he washes off his parents' ankles has no artistic content that can be equated to literature, let alone trying to uncover the hidden meaning of the scene, because the act itself has already transcended any aesthetic experience one can come up with. Owns. The lack of new knowledge, both practical and emotional, is so great that one begins to view culture as an accessory, a crutch for one to use if one is not living a full life. The assumption that culture expresses something is, in the end, a preposterous idea. “How are we going to talk about the war?” Asked the people of the Ukrainian theater. I don't know, maybe we shouldn't talk at all. All the words we produce sooner or later as we desperately try to catch the collapse,

The explosion in our heads, perhaps accumulating somewhere and forming an unnecessary, irrelevant layer.

–

So perhaps it was my father's illness, my grandmother's dementia, or a cockroach sneaking into the apartment one summer when it wasn't convenient that kept me from becoming a dedicated cultural worker. When a new world full of blood and war and flesh and death seemed so dangerously close, I fell silent, feeling ashamed and embarrassed and bitter and nostalgic for all forms of writing that had no stated purpose of being useful.

When the war came, I turned to journalism with relief. As a reporter, I visited the first towns and villages to be liberated from occupation, finally rid of the embarrassment of being seen as a cowardly intellectual, an out-of-touch academic, and the last person to be saved in a shipwreck. The desire to stand up for shameful justice was there, as was the sense of physical urgency, but it was my attempt to save myself from being hideously useless, from being unforgivably negative, from being turned into the hideous white museum director in the movie. Square, who was poorly disguised, made himself known. Thank God, I was telling myself that I was not resisting the invasion, with a small book of poems in my hand – what a pathetic sight.

It was only through a few cracks that things like literary writing and the kind of emotion associated with it began to seep into the new militarized everyday life. It could be a brief glimpse of a picturesque landscape on a colleague's billboard I passed, a fairly ordinary sunrise or sunset in my dreary neighborhood, something I've never been sensitive to, or a phrase stuck on my bookshelf that has never happened before. Me would have felt the same amount of impact. It became even stronger when we survived a number of attacks in March while watching Wong Kar Wais Chongqing ExpressAlthough it sounds desperate, the film was still equally overwhelming, leaving me dreaming that I was making my way between lemon-yellow rooms, late-night bars, and cheap hotels that seemed far away.

sky

After all, it cannot be overstated what it means for a speck on the wall to suddenly look like a beautiful cloud while listening to bombs explode in the distance. Admittedly, I am deeply opposed to any form of escapism (and culture as its highest form), but it was during those days that I secretly fell in love with dreaming and writing for the first time since I was a child. I was obsessed with the idea of helping, of being useful, of having something that undeniably justified my existence; I couldn't see any point in inventing lyrics, let alone pretending they meant anything, because they couldn't heal bodies or restore light. But at the same time, I was very attracted to the idea of taking another step into some dimension that wasn't trivial and real. I dreamed of standing in the middle of the street in an unexplored city, like Seoul or Tampa, the night lights of South Korea in the 1990s, and the national park in Singapore. Which I memorized and remembered more than all of them

The first weeks of the war were great cinematic images of Korean cyclists, part of my vivid morning dreams, things I had never seen, cities I had never visited. As much as I hated meditation, it somehow became the only thing I really enjoyed, and the only thing that helped me come to terms with my body.

“Who has the privilege of not knowing?” It's on my mind as I write this article. As a follow-up question: Who has the privilege of sticking to another topic that is less shocking and more seductive? Who has the right to sift out the latest disturbing news and spread the word about Gilles Deleuze, Renaissance art, ancient street vendors, Manhattan's obscenely high beer prices, and the precarious state of semiotics, all in the safe frame of a panel discussion as a hedge between himself and the “controversial topic?” ? Am I jealous of them enough to be disgusted by them?

Although the gap between reality and vanity may be a bit contrived (it's not quite one or the other, by the way), the idea of writing as a major lifelong vocation no longer occupies my thoughts. Of course, you can honestly call the words a “major contribution,” until anti-aircraft missiles, pharmacy receipts, bad bugs, or something else begin to shape your future much more than all the books you've read.

However, it is a somewhat bitter irony that although I feel such a genuine aversion to words, I prefer them to other means of contribution. Could they really be valuable? Why do I still want to justify their existence? Is there any way at all to justify musings and daydreams? Well, even Morse code meant to convey a particular message could be considered a poem, smart scholars say. And I probably wouldn't object, but instead I chose to take it as it is.