Johnson has been at the shelter every night since he got off the waiting list on Thanksgiving. If he misses check-in, he risks losing his bed. The sun is setting, and the first snowfall in over 700 days covers the ground.

On a freezing night in a city of nearly 5,000 homeless people, Johnson doesn't want to be where he found himself last fall during his first extended bout with homelessness, riding the Silver Line from end to end to get some sleep.

Every liquor store is a temptation.

“I'm trying,” he says.

Robert Vaughn, 69, lines up for dinner at Central Union: beef stew. Although his breathing is labored — the third stage of emphysema — he is cheerful. He says he has been sober for 11 months, one of the longest periods he has been since he left home around 1967.

Central Union, founded in the 1880s to serve Civil War veterans, was a 14th Street landmark until about a decade ago, when it was replaced by condos. Its current location — two blocks from Union Station and across the street from a luxury hotel — serves as a reminder of the people in desperate straits stranded among policymakers, commuters and tourists at the foot of Capitol Hill.

After years of living in other D.C. shelters — “hell holes,” Vaughn says — he is in a long-term recovery program at Central Union. He lives in a four-man suite on the third floor of the shelter, after you exit the second floor residence. He reconciled with his four adult children and agreed to a no-fault divorce from his wife. He says he no longer smokes crack. In his novel, he is no longer a “hurricane” that destroys women’s lives.

“I was living differently,” he says. “Now, I'm doing all the things I was asked to do years ago.”

Johnson and Vaughn report to the Central Union Church, which is separated from the cafeteria by a folding wall. Johnson reported that his job interview went well. He was told he was at the “top of the short list.”

“I try to remain optimistic about any opportunity,” he says. “If not, depression sets in.”

Before the nightly ritual – reading the rules of the sanctuary – a chaplain welcomes guests.

“You make it in this cold,” he says. “Thank him for the heat. Thank him for the shelter. Can we praise the Lord tonight?”

Non-denominational Christian ministry begins. The leader of the service — Pastor Norman Thomas of First Baptist Church in Glenarden, Maryland — delivers a sermon on names. Johnson scrolls the recruiting website as he listens.

Thomas says that the names God gave to his creatures have power. Whoever bears these names must abide by them. In “Black Panther,” Prince T'Challa defeats a formidable foe by summoning the power of his mighty name, he says.

“What is it for you Name?” Thomas asks. “What did you do for you What does the name mean to you?

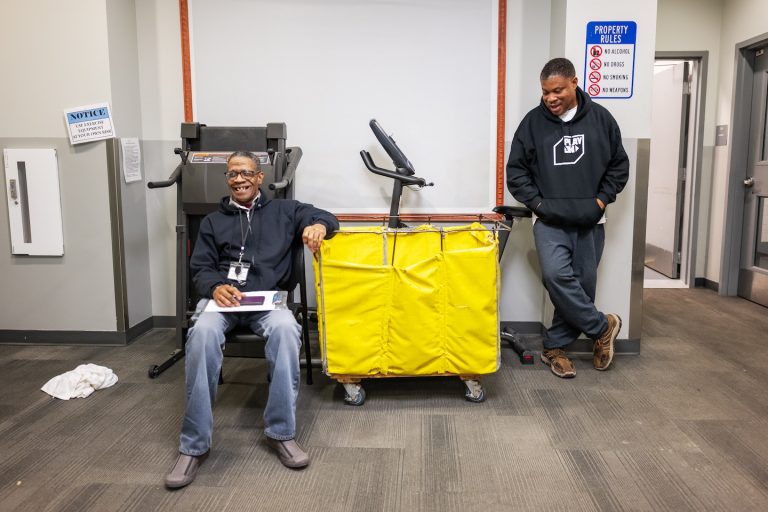

Before lights out, Johnson and Vaughn head to the lobby on the second floor of Central Union. Men have volunteered for housekeeping duties.

Johnson monitors the mandatory shower line, making sure no one exceeds the seven-minute limit. Vaughn monitors “bathtub rooms” in college housing, where residents store personal items in plastic containers.

Vaughn takes the elevator into a small hallway crowded with chairs and a television. A handful of sleeping mats cover the floor. These are for visitors suffering from “hypothermia” – men who cannot be turned away during a hypothermia alert even though the dormitory is full. In the dark, they huddled in their coats, bags surrounding them.

At 7am, it's time to figure out where to spend tomorrow.

The lights are on, but the world is still cold.