Jeddah-born artist Dana Awartani talks about creating contemporary works that honor the past

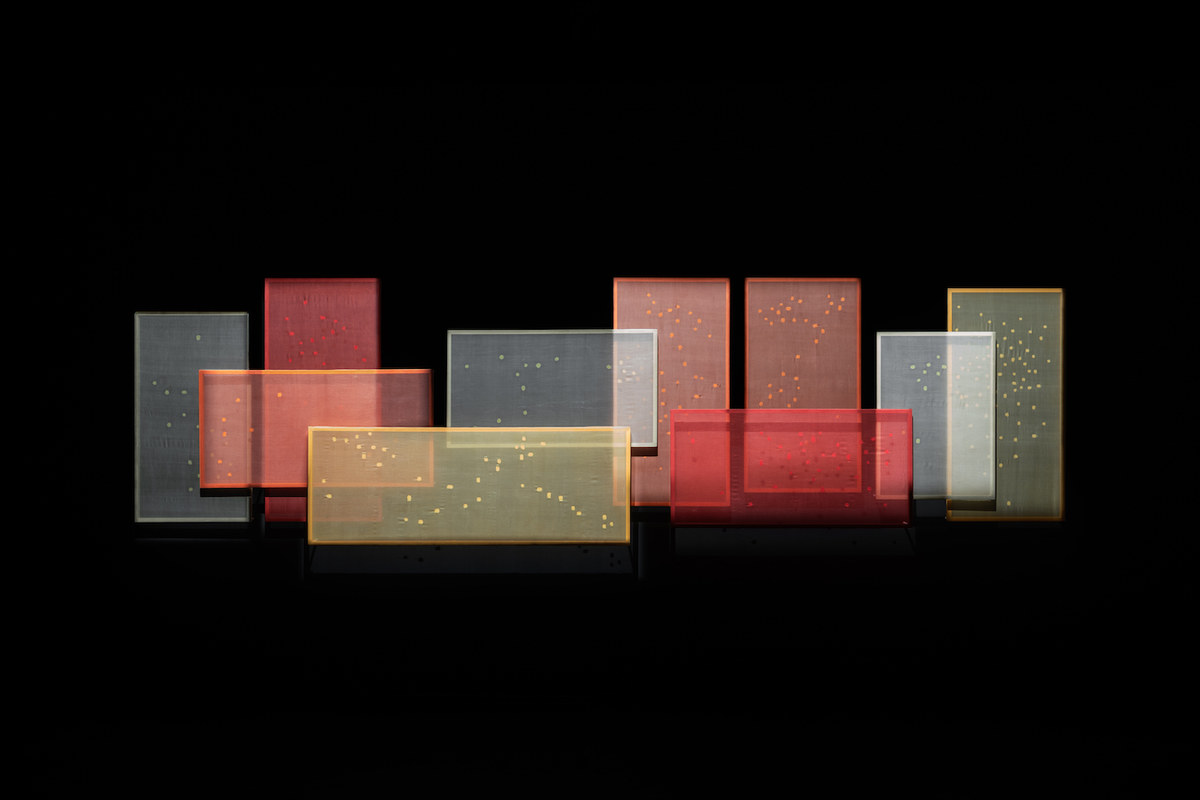

Dubai: At the Diriyah Biennale of Arts, Saudi-born artist Dana Awartani, of Palestinian heritage, created a dreamy, otherworldly series of 10 silk fabrics in earthy hues of ochre, red and green placed on wooden frames and mounted on the wall like overlapping, semi-transparent panels.

The installation – “Come, Let Me Heal Your Wounds” – draws from research into Ayurvedic dyeing, which is used to make clothing with purported healing properties. To create this work, Awartani collaborated with craftsmen in the state of Kerala, India.

The artist also identified 355 cultural sites destroyed by conflict and violence since 2010 in Syria, Tunisia, Libya, Iraq, Egypt and Yemen. She marked each location with a piece of silk, creating her own intuitive map of loss. Awartani, in cooperation with local craftsmen, repaired the fabric and repaired each hole by hand.

Dana Awartani, “Come, Heal Your Wounds” (2020), presented at the Diriyah Biennial of Contemporary Art 2024. (Attached)

The work points out the fragility of cultural sites throughout the Middle East and North Africa region, and serves as a call to protect ancient monuments and Arab culture and traditions in general.

“You have this erasure of history that is happening in the Levant, and in Gaza now, and I felt it was important to use my training in traditional arts and aesthetic language to talk about issues relevant to the region,” Awartani tells Arab News.

Awartani's works, which cover a variety of media – including drawing, painting, textiles, multimedia installations and film – are inspired by the rich heritage of Islamic art, especially “sacred geometry.” abstraction; And traditional crafts. She combines these influences with contemporary methods to present works imbued with compelling aesthetic qualities and philosophical depth. Much of her work uses locally sourced materials, as well as vernacular and ancient design techniques to provide a dialogue between the past and present of Arab culture.

(supplied)

“The memories and experiences of the people I collaborate with also become part of the work,” she says, adding that traditional arts “are disappearing, and people no longer use sacred geometry; they become part of the work.” “People don’t work with their hands anymore.”

Engineering is the focus of her animated film “Listen to My Words” – which is also featured in “After the Rain.” In it, the gray background is gradually filled with a finely drawn geometric pattern inspired by jellies and mashrabiyas – mesh screens used in traditional architecture to regulate light, airflow and heat. Jaalis were also used to protect women from the sight of men.

Awartani explains that the film is inspired by the story of Noor Jahan, the wife of the Mughal emperor, who is said to have played a leading role in the government in the 17th century behind Jalis, whispering orders to her husband. It is captured through contemporary readings of Arabic poetry written by women centuries ago, giving them a platform and resonance in the present.

Awartani’s 2023 work, “When the Dust of Conflict Clears,” in which she collaborated with construction workers from Syria. (supplied)

Integrating traditional practices into contemporary artistic discourse is central to Awartani’s art – she is currently pursuing a degree in Islamic lighting. The work she created after receiving her master's degree from the Prince's Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London focused heavily on sacred geometry. It is something that still has great influence (as evidenced by Hear My Speech), but is less influential than it used to be – a shift she attributes to “recent events in the Middle East, with the ways in which current wars have destroyed heritage and civilization.” . Culture of the region. This really changed my perspective.”

Regarding her previous work, she says: “When I graduated from the Prince’s School, it was difficult to stop training because you are continuing an art form that has been around for centuries, and there is a certain level of responsibility that comes with that.

“There are a lot of people who take something old, like traditional crafts, and innovate without understanding it. Sometimes I find that a problem. For a long time, I was still trying to hone my skills and learn as much as I could about traditional arts while still using them in a contemporary way through concepts related to Islamic geometric patterns.

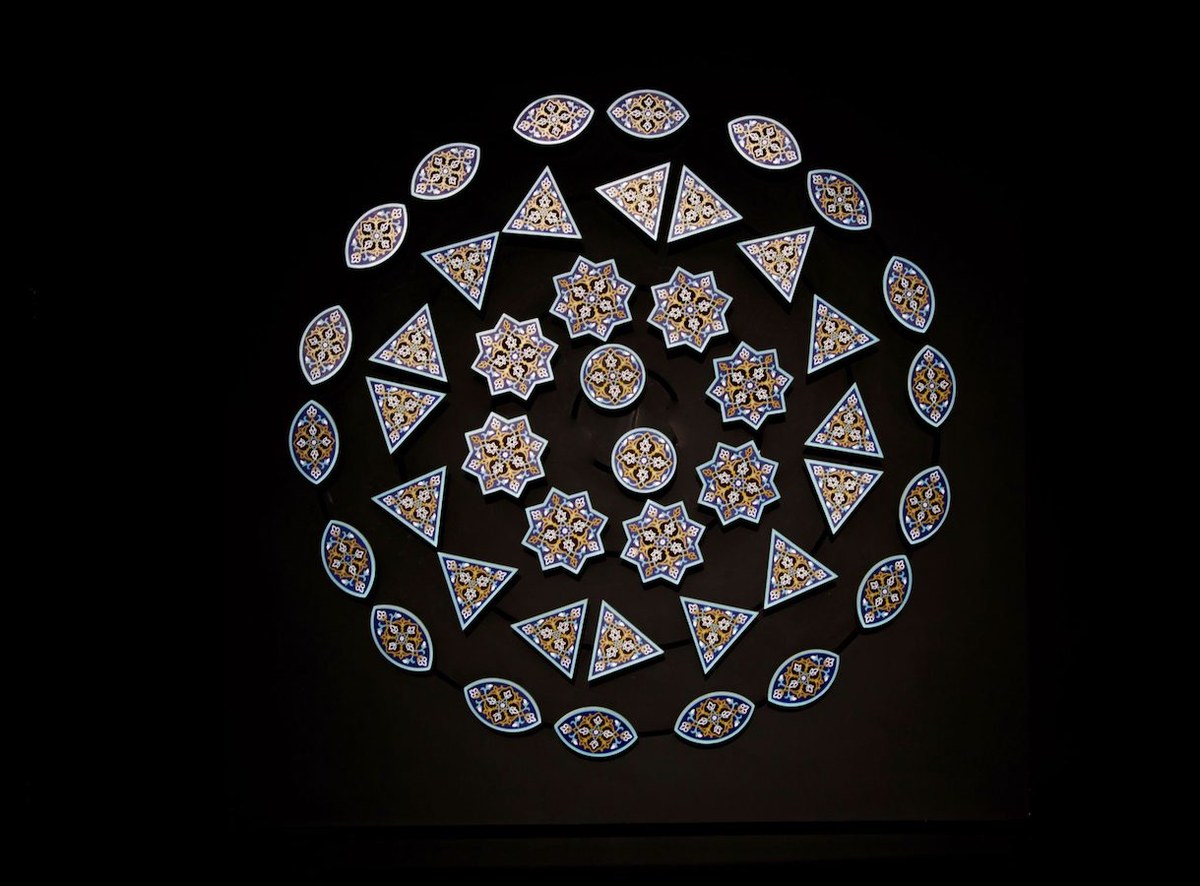

All celestial bodies swim together, each in its orbit, Dana Awartani, 2016. (Attached)

Awartani says that her initial interest in sacred geometry was a way to “understand the world from a different perspective by seeing the harmony in nature and the universe through the lens of geometry and numbers.” Sacred geometry is also a way to connect with its heritage.

“As Arabs, we have grown up around these fine arts, and we are surrounded by them at every corner, but we are not aware of them,” she told Arab News in a 2014 interview. “You can see geometry all around you, like in mosques for example. I was looking for a path to follow – deep down I felt a longing for it. There is an inner and outer beauty that tells a story behind every structured piece; there is no randomness when it comes to creating such Pieces.

Not only has the theoretical aspect of Awartani's work transformed, but the way she creates it has also changed in recent years.

“It's more collaborative now, involving different craft communities,” she explains. “While I used to draw and make artwork on paper, I now incorporate the work of traditional craftsmen into my work.”

In last year's film When the Conflict Settles, for example, I worked with trainee construction workers from Syria who had been displaced by war in their homeland and were living in Jordan.

“This meeting between different artisans to promote knowledge exchange is what I am really excited about right now,” she says. “This is an exchange of knowledge and an exchange of culture.”