This article was published in Bitcoin Magazine “The question of inscription.” Click here For your annual subscription to Bitcoin Magazine.

Click here to download a PDF of this article.

Rankings have been a polarizing phenomenon for most Bitcoin subcommunities – with the exception of miners.

The meteoric rise of Bitcoin's new native NFT standard has dominated the discourse for months, as Ordinals flood the block space and transaction fees soar to multi-year highs. According to critics, these transactions are, at worst, an attack on Bitcoin that has tarnished the sanctity of scarce block space; At best, they are ridiculous coins, playing tools for gamblers who belong to casino chains like Ethereum.

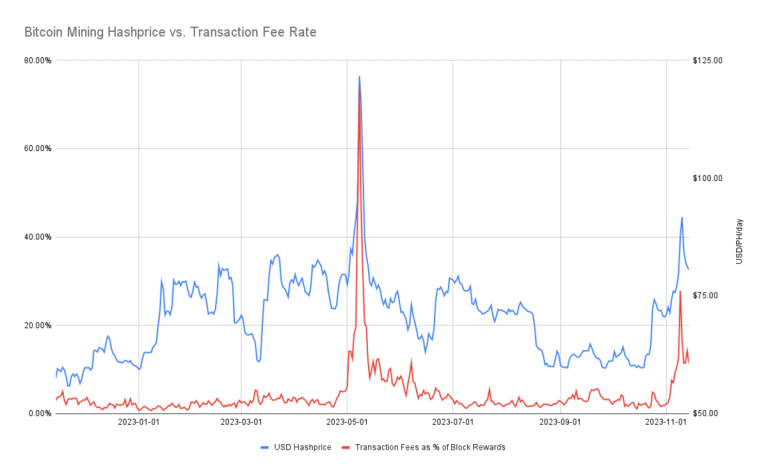

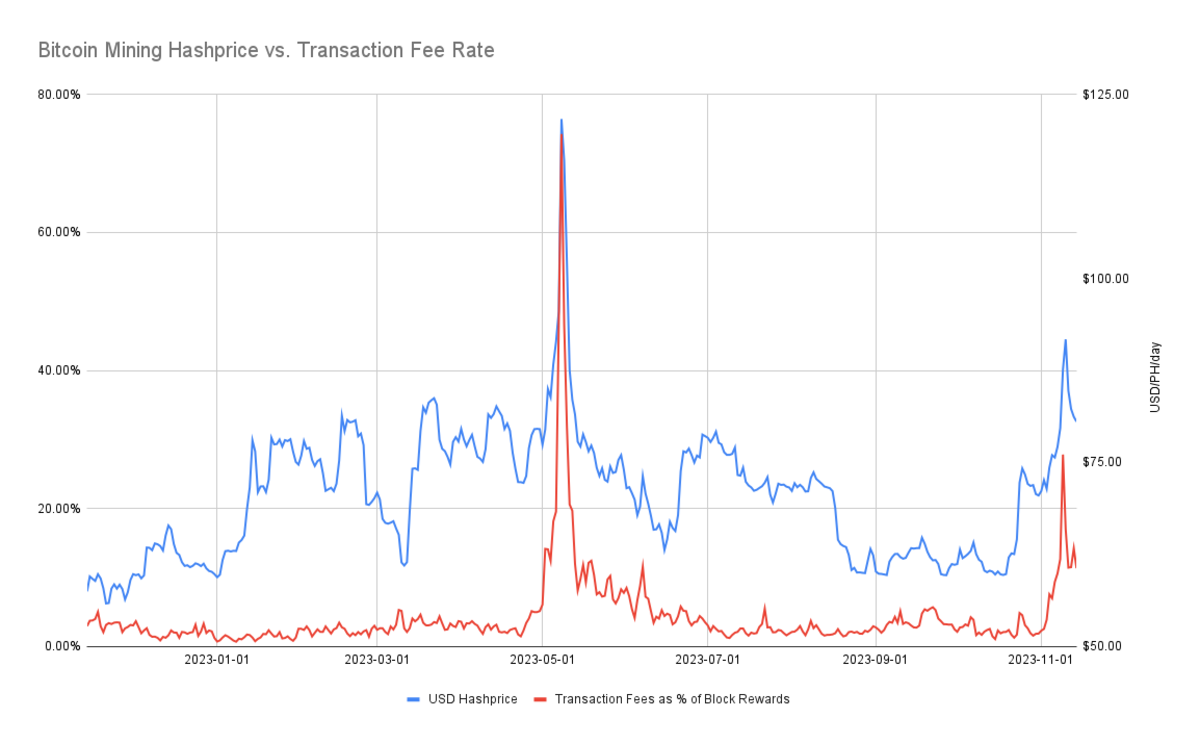

Well, miners don't care if their coins are bad. They care about making money, and Ordinals gave them a boost in revenue at a time when mining income was at one of its lowest levels ever. Many miners have embraced – or at least, are ambivalent about – the arrangements/patterns, since they received a much-needed boost to Bitcoin mining profitability when many miners were breaking even or unprofitable.

Hash rate is a measure of the amount of USD (or BTC) miners can expect to earn per unit hash rate (for example, at $80 per PH/day, a miner has 1 petahash of mining rigs – approximately 10 rigs A new generation ASIC like the S19j Pro, for example – can earn $80 a day).

Due to their positive impact on retail prices, Ordinals, a technical advance that few could have predicted last year, has found itself at the center of discussions regarding the economics of Bitcoin mining, discussions that are more relevant to each block that brings us closer to the fourth block of Bitcoin lowering support. To half.

I'm not writing this to preach to anyone to become a tidy-up. I, personally, don't really understand the appeal. But I think they're important in the context of Bitcoin's ever-dwindling block support, so they're worth studying to understand how they impact block space and mining economics — and what developments like them might mean in a future where miners live solely on transaction fees.

WTF is my ranking, anyway?

In NFT parlance, people use ordinal and engraving interchangeably, but the individual terms refer to two different aspects of the NFT standard.

An engraving is a piece of art or digital media, while an ordinal number is technically the specific number of an engraving to determine its place in the grand scheme of all other engravings. Another way to view this is that the engraving itself is an NFT, while the ordinal number is the number used to identify the individual engraving.

The data for each inscription is located in a separate witness section of the transaction. As such, unlike other NFT standards, the actual art, digital media, or data is uploaded directly to Bitcoin's blockchain. Since the inscriptions are entirely on-chain, you could argue that they are the purest form of NFT available because they take advantage of the immutability of the blockchain.

Not all engravings are created equal

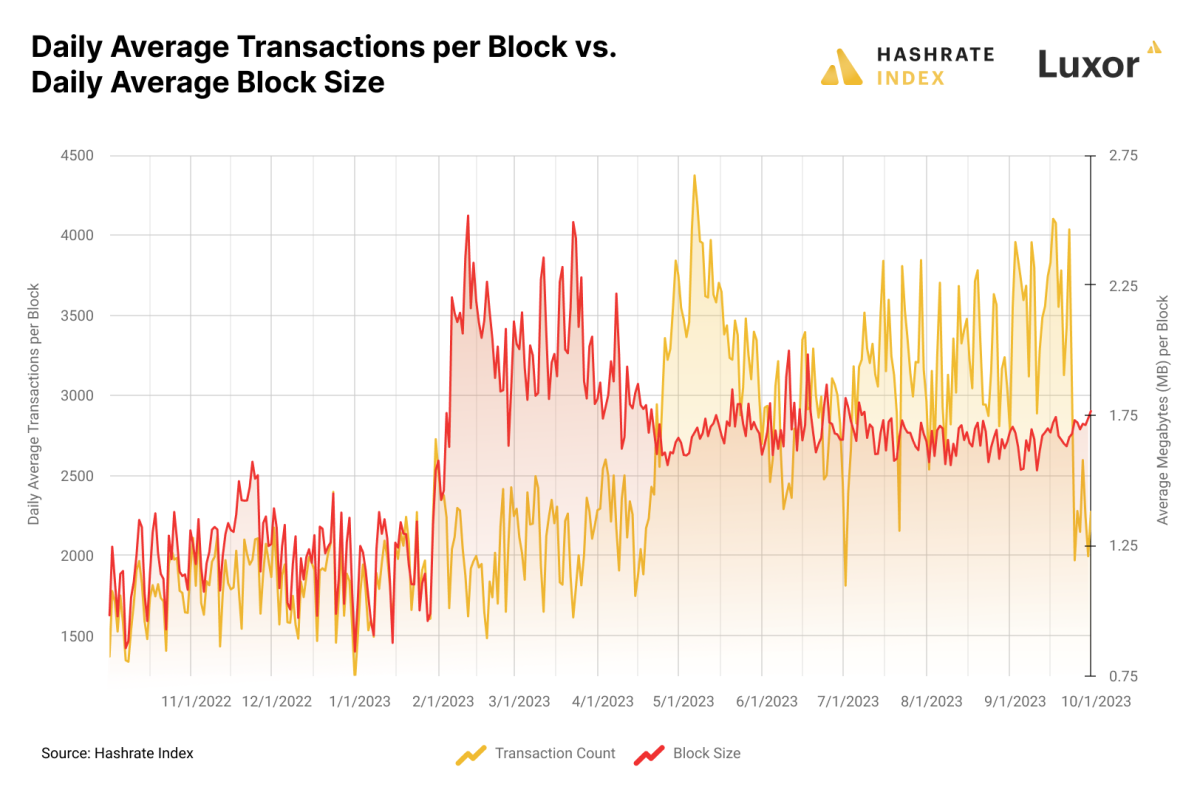

When you understand that inscriptions are actual data on the chain, you can appreciate some of the criticisms and concerns from detractors; If a bunch of copies of an NFT are recording JPEGs, dicbutts and “God knows what else” on-chain, this rules out economic (and perhaps necessary) transactions.

This concern is exacerbated by the fact that arbitrary data per registration benefits from a transaction fee deduction. As a measure of scalability, Bitcoin's Segregated Witness upgrade modified the transaction structure so that the witness data for the private key signature and public key were moved from the transaction hash field to another part of the block. Bitcoin discounts SegWit data, so it requires fewer satoshis per byte in transaction fees to make transactions. The arbitrary data for the engraving is in the SegWit field of the transaction, so it is entitled to a SegWit discount. Cue the pitchfork.

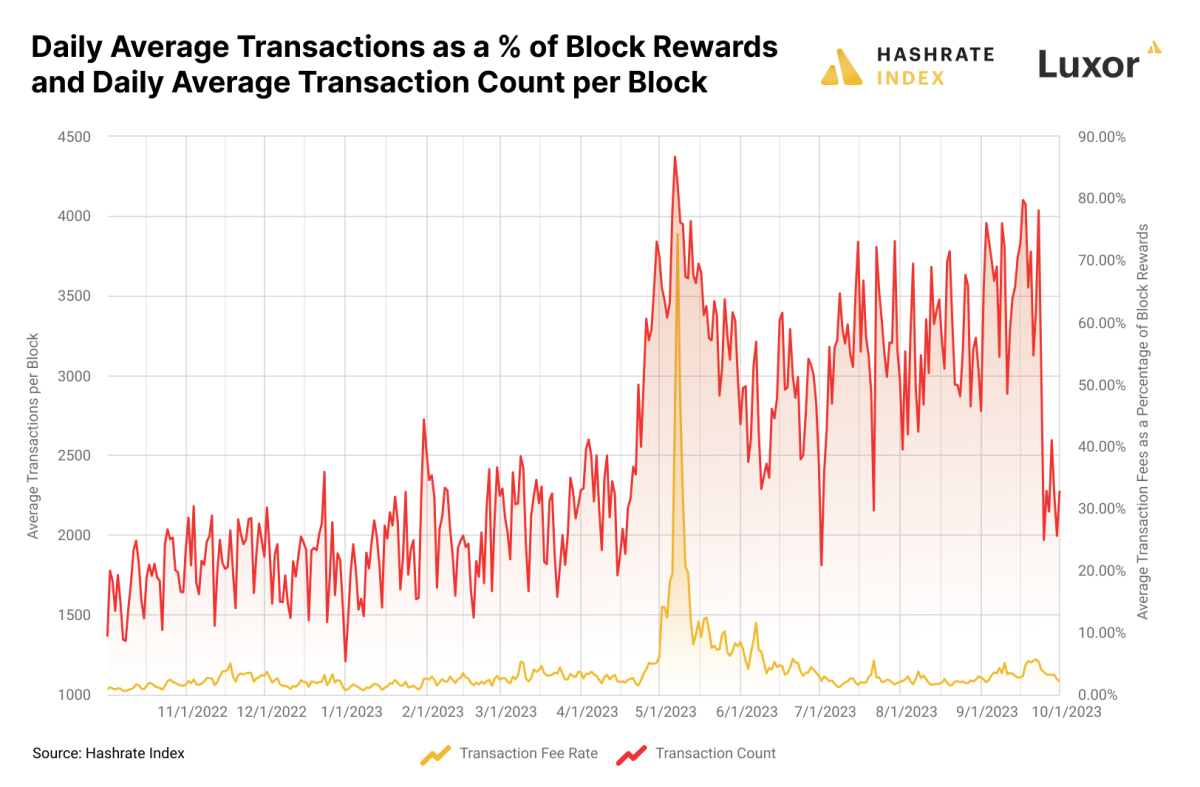

This discount is the reason why transaction fees did not increase significantly, despite the first wave of image-based prints that clogged the block space in February/March/April; Block sizes ballooned as leading miners flooded the blockchain with thousands of JPEG files of the first miners' blocks, but all of these benefited from SegWit's 4-to-1 data discount versus regular transactions. Perhaps counterintuitively, transaction fees rose only after text-based engravings that were less data-intensive than BRC-20 tokens became the more common type of engraving.

The so-called BRC-20s (a reference to Ethereum's ERC-20 token standard) are a loose form of tokens. I say loosely because they are actually just ordinal numbers in a chain defined by Bitcoin's OP_CODE function, where each “token” is itself an OP_CODE transaction that specifies where the token is in the specific BRC-20 chain. It looks like this: Someone (God knows who) posts an OP_CODE transaction that sets the maximum supply of the token chain, the ticker, and the maximum mintage for each transaction. Once announced, anyone with the technical knowledge can mint tokens on the chain.

These OP_CODE transactions don't benefit from SegWit's data discount, so they cost a pretty penny more than image-based engravings. But they also have an advantage that photo engravings don't: a minting function, which provides Ethereum NFT-like incentives for collecting these engravings. The Ethereum NFT chain typically has minting contracts where anyone can create new NFTs on the chain by interacting with the contract. This is part – if not all – of the appeal. Minting an NFT is like opening a digital pack of Pokémon/baseball/Magic: The Gathering cards – maybe there's a rare card in that next one!

And while there isn't necessarily an opportunity to mint a rare BRC-20 (because they're all the same), there is an opportunity to mint a bunch of NFTs in an exciting new series. Why anyone would care about having ORDI/CUMY/RATS #1 or #100 or whatever, I don't know. This is perhaps the greatest expression of Bitcoin's Biggest Fool Theory yet. But the fact is that they do, and the BRC-20 mint incentives have contributed to the largest wave of Bitcoin transaction activity ever.

Through a combination of fee wars and the fact that NFTs don't benefit from the SegWit discount, the BRC-20 has provided a veritable fee feast for Bitcoin miners, but not quite in the way you might think.

Identify collateral damage of transaction fees

The bulk of transaction fee increases in 2023 did not come directly from fees associated with Ordinals; It came from the pressure of indirect fees on other transactions.

According to data from independent analyst Data Always's Dune dashboard, as of November 12, 2023, miners have received $70.3 million in fees from Ordinals. It sounds like a lot, but it represents only 19.4% of the total $368.2 million transaction fees that miners have earned since registrations first appeared on December 14, 2022. To break that down further, there were 40.2 million registration transactions, which equates to 30%. Of the total transaction volume since December 14. So, registrations accounted for a third of transaction volume over the past year, but only a fifth of total fees.

As for other fees, many of them result from indirect fee pressure from the prints – that is, fees that do not come directly from the prints themselves, but from the pressure that the prints exert on the average transaction fee needed to clear a Bitcoin transaction. Within a reasonable time frame.

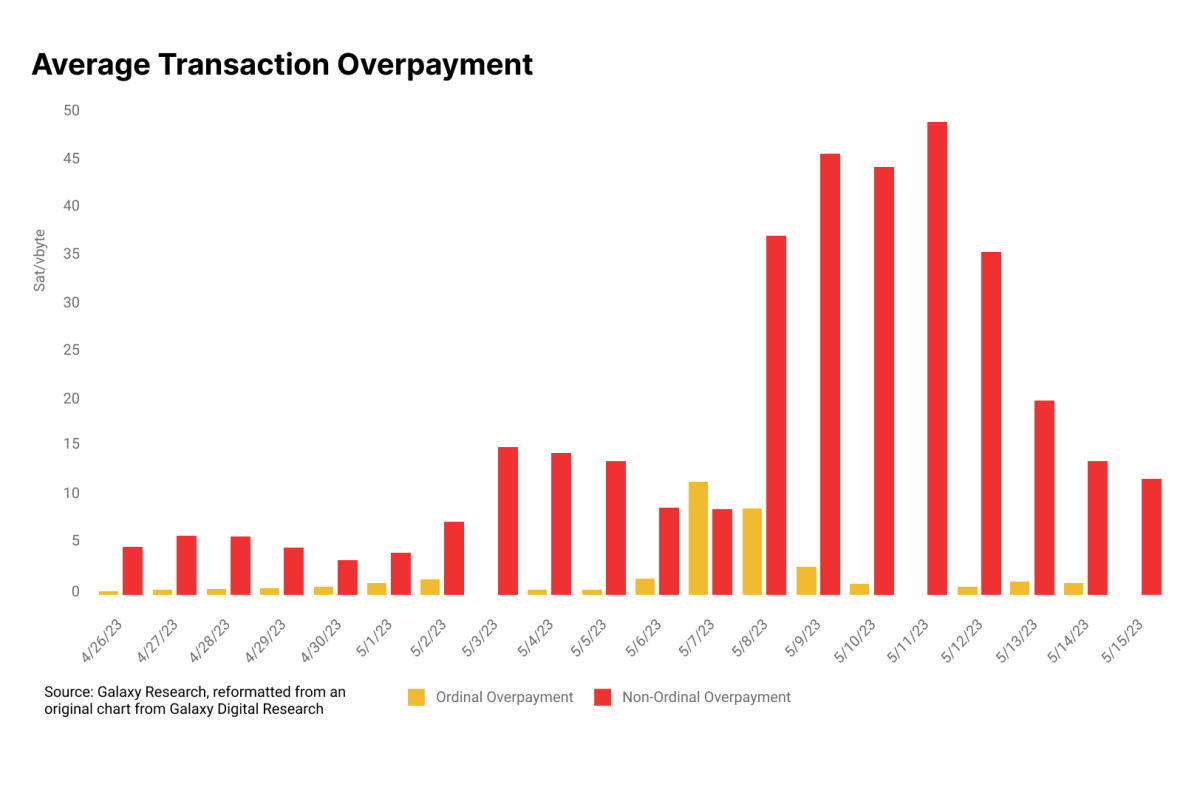

Galaxy Digital Research examines this dynamic in a report titled “Bitcoin Patterns and Ordinals: A Mature Ecosystem.” Rampant engraving activity leads to memory pool congestion. This is especially true during BRC-20 mint events, as the first-come-first-served principle of minting incentivizes bidding wars where miners are the first to mint a series. This raises the minimum average transaction fees and, as Galaxy Digital Research points out, leads to “overpayment” of transaction fees from various transactions. They define overpayment as any fee in a block that is larger than the average transaction fee for that block. For normal transactions, this overpayment can come from transaction fee estimators in wallets or exchanges or from general user ignorance regarding the structure and dynamics of transaction fees. Some users may also need to speed up transactions for any number of reasons, resulting in overpayment. For notation transactions, Galaxy Digital Research says “voluntary overpayment” was common during times of high activity and popular mints.

This graph quantifies overpayments for registration transactions and all other transactions to illustrate the dynamics that Galaxy Digital Research identifies in its report. When Bitcoin notes became backlogged in April and May — the hottest time frame for registration activity to date — the majority of transaction fees during this time actually came from user overpayment for financial transactions, not from the registrations themselves. These users can probably make it easier on themselves by not using the transaction fee capabilities built into their wallets and exchanges.

Mixed blessing

Inscriptions are a blessing and a curse. It's a godsend for miners, but it can be a pain in the butt for other Bitcoin users, especially those who have to send transactions on the network every day.

However, Blockspace is an open market. So I don't have to like Ordinals to realize that it's not my place to monitor someone else's spending. Nor do I have the right to censor transactions that pay for block space in the f(r)ee market. That's part of the point of a permissionless blockchain, after all: to make transactions that others don't want to make.

This article was published in Bitcoin Magazine “The question of inscription.” Click here For your annual subscription to Bitcoin Magazine.

Click here to download a PDF of this article.