At the age of eighty, Sly Stone wrote his memoirs. The musician reflects on his ups and downs with brutal honesty, recalling his early fame, drug use, arrests and failed comeback attempts.

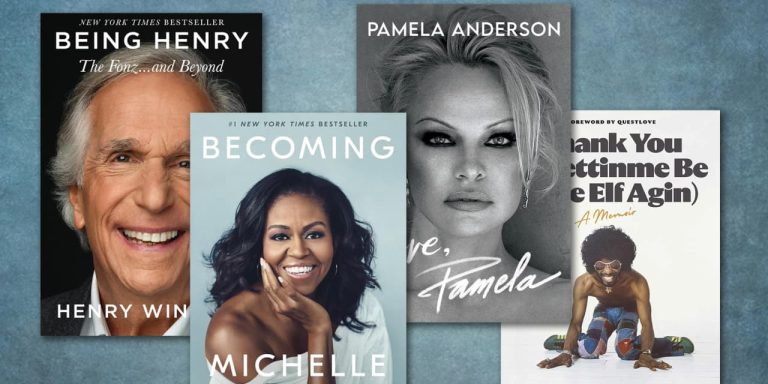

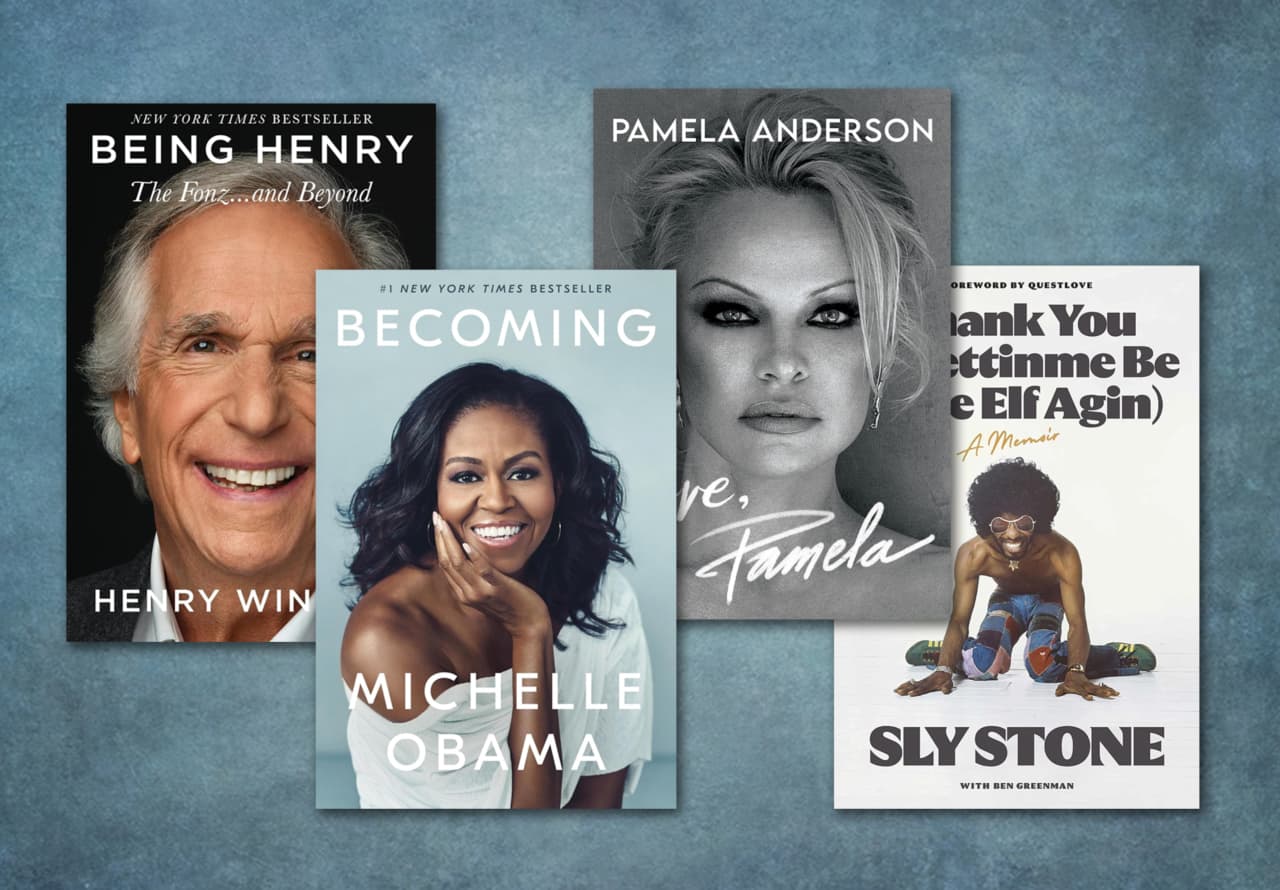

Celebrity memoirs are nothing new. Their often harrowing content can offer cautionary tales while educating and inspiring readers. In the past year, we've seen a torrent of celebrity memoirs published, including Stone, Jada Pinkett Smith, Patrick Stewart, Dolly Parton, and Kerry Washington.

What's new is the number of non-famous retirees writing memoirs. Eager to document their lives and enrich their heritage, they reflect on how they lived, who they loved and what they learned.

is reading: How Chocolate Master Jacques Torres found success as a chef, father of young children, and retirement saver at 65

It helps to have laid the foundation. This is better than waking up one day and declaring: “I am going to write 270 pages about my life.”

If you've kept a journal for years or filled a binder with occasional musings, colorful anecdotes, and newspaper clippings, you already have a head start.

“I started parts of my memoir years ago,” said Dennis LeDoux, 77, a writing coach who specializes in memoirs. “It's only in the last two or three years that I've gotten serious about it.” His memoir, French Boy: A Franco-American Childhood in the 1950s, was published independently in October.

The key to writing a memoir is to move forward in stages, LeDoux says: Instead of starting from scratch in retirement, pave the way by telling one story at a time throughout your life.

“Think of your memoir as an anthology of stories,” said LeDoux, who lives in Lisbon Falls, Maine. “Stories can be about a poignant experience, a relationship you had, or any other specific memory.”

To shape your narrative, choose a central theme. This guides your organizational structure and adds purpose to each page.

“I wanted my memoir to make a statement about my background,” LeDoux said. “Writing it was therapeutic and helped me understand and accept difficult events.”

Even if you have collected years of stories as a starting point for your memoir, the process of integrating the stories into a cohesive collection takes a lot of effort. Muster your discipline to stick with it and finish the job.

To make progress, set aside time each day to write. Even if you only commit to 30 minutes a day, keep at it.

“Once you get into the habit, it's a lot of fun,” LeDoux said. “Otherwise people might give up or think, ‘I don’t have time to do this.’”

If you're not used to writing, consider joining a writers group. Check if your local library, university, or adult education center offers such a program.

is reading: Why are cassette tapes making a comeback? And it's not just a fad

After retiring as a theater professor at Wright State University, Abe Bassett joined a writers group led by a colleague. This led him to collect dozens of stories, which he then categorized under different headings (growing up with my father, his time in the army, etc.).

Bassett, 93, author of “The Father of Abraham’s Son,” said, “The best stories reveal something about the writer.” “Stories should be relevant and interesting” – not just for you, but for your readers as well.

Like LeDoux and Bassett, Dorothy Lazard drew on a collection of written stories as the basis for her 2023 memoir, What You Don't Know Will Make a Whole New World.

“I wrote it all the time about important moments in my life,” Lazard said. “I've been writing a diary since I was a kid.”

Eager to celebrate her 50 years in California, she wrote a memoir to trace her experiences and how they enabled her to grow and gain wisdom.

Like many memoirists, Lazard realized that reaching a wider audience required a leap of faith.

“I saw that I was writing for someone else, not just for myself to meet a special need,” she said. “It can be frustrating. It can be really hard to know that you're going to be looked at by strangers. It can cause external pressures and external judgments,” which can lead you to self-censor your work.

Lazard, 64, overcame this challenge by responding to memoirist Tobias Wolff's observation that memory has its own story to tell.

“I wanted to tell stories that stuck with me,” she said. “I tell people: This is a story my memory had to tell.”

If you're thinking about revealing intimate details about family and friends, Lazard says, you should be prepared to ask, “What do they think about what you wrote?”

As a precaution, you can invite them to review your manuscript and provide feedback. But think twice before you bend over backwards to accommodate them.

“Don't give away your voice by telling a story from someone else's point of view,” Lazard said. “Be committed to the story you want to tell.”