On October 29, 1923, a council in Ankara declared the formation of the Turkish Republic and elected Mustafa Kemal Ataturk as its first president. The new republic promised a fresh start after more than a century of conflict that had seen the Ottoman Empire shrink and collapse.

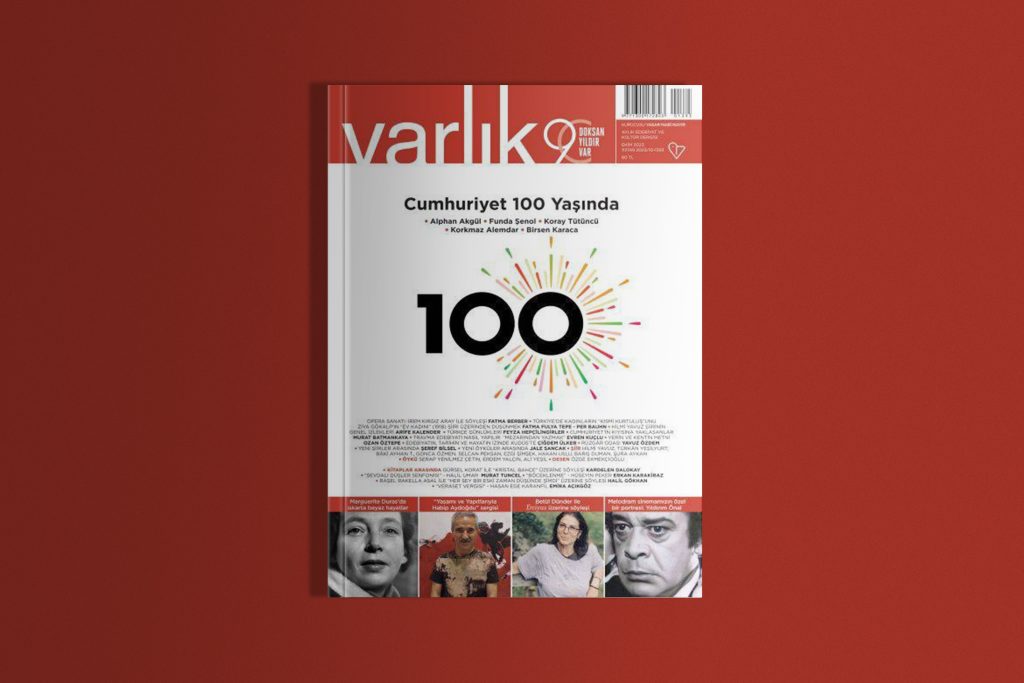

Presence He marks the national centenary with a collection of essays on the achievements and failures of the Kemalist Republic, a radical project of sweeping reforms of laws, language, and education aimed at building a modern, secular, and independent nation.

Republican utopia

Alvan Akgul reflects on Türkiye's 20 yearsyA century-long experience of dystopia and utopia, from the horrors and devastation of World War I and the subsequent War of Independence to the utopian thinking that fueled the early years of Ataturk's republic.

Looking at today's Turkey under Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the AKP, Akgul is convinced that a new wave of idealistic thinking is needed. He proposes to combine modern thought with the inspiration of the past century:

Developing a new economic and moral model through reconciliation [Thomas] Piketty's utopia of libertarian socialism combined with the idea of solidarity in the early years of the republic could enable our republic to rise from the ashes.

Formal history and feminism

The official history of Turkey claims that the struggle for women's rights was born alongside the republic. The narrative whereby the Founding Fathers “granted” rights to women has weighed on women’s backs ever since, Fonda Chenault says, delaying the study of the “courageous and vociferous” movements during the Ottoman Empire.

Starting with these feminist pioneers, she traces a century of feminist magazines and movements that were sometimes aided, sometimes hindered by the state. Today's Turkey is a country where “the AKP's authoritarianism, which began with the Gezi protests and deepened with the 2015 elections, has led to a setback in the struggle for gender equality,” Senol wrote.

An unpopular republic

Koray Totunku begins his examination of the Republic by recounting how he entered university “having without a doubt internalized the Republic's historical narrative, its worldview, and its vision of the future” but then found his certainty crumbling. The Kemalist position has been attacked from the left as an elitist project, and from the right as a betrayal of deep cultural values.

For both of them, the fundamental problem was that the Republic was unable to integrate into society. In reproducing its own values, the Republic was unable to establish a democratic relationship. And because she could not, she would also not be able to fulfill her promises of general well-being and happiness. Because she spent all her energy fighting with her audience.”

Republican media

Korkmaz Alamdar traces the successes and failures of the media system created by the Republic in the 1930s. The original Kemalist vision was for trained and educated journalists working in independent media organizations under the protection of strong labor laws. Although some of these elements are sometimes present, the demands of politics, international relations and business are increasingly eroding and undermining it in various ways.

However, Alamdar says, there are lessons to be learned a century later about “the importance of independent media institutions and what it means for journalism to be strong in the face of power and capital.”

Also to search for: In a series of interviews conducted over the years with individuals from different generations, Bersen Karaca offers a personal history of how the Republic changed lives through educational reforms.