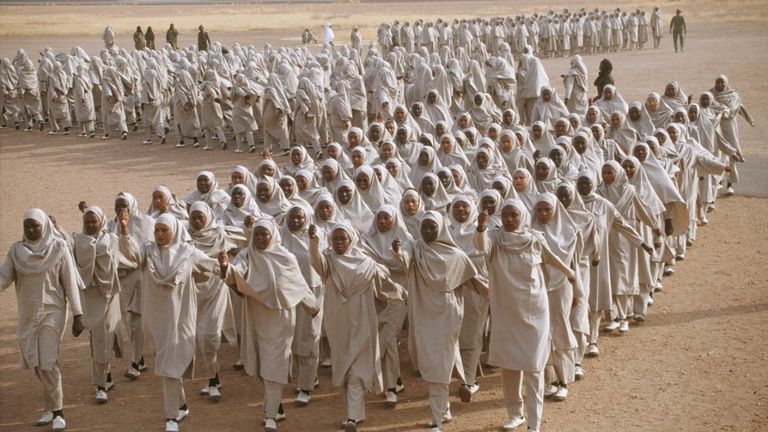

A schoolyard in Port Sudan, where children studied and played before the war, has been transformed into a combat training site for women and girls.

Students, teachers and housewives gather daily to learn drills and how to fire AK47 machine guns from army officers.

Some are here out of loyalty to their sons, fathers, uncles and brothers, the conscripts who have been deployed across the country in the SAF's war against the RSF.

“We support the army! They don't need us but we are here to support them,” they shout excitedly under the eyes of their new commanders.

One of the women said, crying: “My son was killed by the Rapid Support Forces. He was an officer.”

Others are here out of sheer necessity.

Another said with fire in her eyes: “We are here to defend ourselves and our children, everything we are defending in the face of everything we have lost.” “We've seen a lot.”

She told me that the RSF killed her nephew and kidnapped her niece, who has been missing ever since.

This camp is one of several training sites for women and girls that have sprung up across the country after Sudanese Armed Forces Commander-in-Chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan called on civilians to take up arms and fight the Rapid Support Forces.

'The scale of the rape is unimaginable'

One of the initiatives behind the recruitment in Port Sudan is called “Kandakat” – meaning “Nubian warrior queens” – a word used to describe the women who led anti-regime protests in Sudan’s December 2018 revolution.

They see themselves as civic actors working to empower women exposed to severe and widespread violence by the RSF.

Another trainee said in the schoolyard: “The scale of rape is unimaginable. We have met girls in these camps who were raped.”

“I have three girls, and I am here to defend them and myself.”

We promised them not to show their faces or share their names.

As they carry their machine guns, the image of the Nusseibeh sisters comes to mind. This was Sudan's first combat battalion, formed in 1990 by the ruling Islamist party of former military dictator Omar al-Bashir – only about a year after his coup that ended the four years of democracy that followed the 1985 revolution.

Their duties were limited to supporting the army during the civil war against South Sudan, which eventually tore the country into two parts. Déjà vu is far from fantasy.

Risks of radicalization of traumatized women

The name and memory of the Nusseibeh sisters were invoked at the opening of the first training camp for women and girls in River Nile State in August 2023.

The camp was established by the Al Karama Association – established after the war with government funding – and has been linked to the Islamist remnants of Omar al-Bashir’s regime.

This affiliation has raised fears that the camps are fertile ground for the radicalization of traumatized women.

“Despite the ongoing criticism and concerns about these training camps, the number of women joining them is increasing rapidly,” says journalist Dhikra Mohieddin, who has been researching this phenomenon since the first camp opened last year.

“The latest data indicate that the number of female soldiers exceeds 5,000, and observers believe that the increasing incidents of violations against women in this war are closely linked to the increase in the number of female soldiers – especially among displaced women.”

Feminist groups were outraged by the use of vulnerable women

But even as more civilians join the training, feminist groups continue to decry the militarization of vulnerable women.

Khadija, a 23-year-old volunteer and activist and a leading member of the Red Sea Women's Committee, understands the motivation behind recruitment but fundamentally rejects the militaristic state – whether the army or the Rapid Support Forces.

“They feel that this can be a safety net for them and the only option that can save them from the conditions of the country,” she says.

“I personally don't think this is the only solution or thing that can provide complete security.

“Not all options have been explored. There need to be workshops, meetings and forums to discuss solutions – discussions we have not been able to have since the beginning of the war due to the security environment.”

Port Sudan, the city she calls home and where she has marched and chanted for civilian rule, is now heavily militarized – with checkpoints, an 11pm curfew and an overbearing security presence.

The wartime capital is now a base for military command and government offices, while sheltering thousands of displaced people in schools, hostels and even warehouses.

Click to subscribe to Sky News Daily wherever you get your podcasts

The cost of rent and living has risen and job opportunities have become increasingly scarce.

“We are a hospitable country, but we have been affected by the influx of refugees,” says Khadija.

“But we chose to stand by them because we know that this could happen to us and we might also have to be displaced – we feel their suffering.”