- The strong El Niño phenomenon is expected to remain in place through the spring.

- The strong El Niño winters of the past were different in several ways from what we saw last winter.

- This could include a colder, wetter South and a snowier Mid-Atlantic region.

- However, El Niño is not the only driver of weather patterns.

El Niño will likely continue to be stronger through the spring, and that could mean significant changes in snow, rain, and temperatures compared to last winter in the United States.

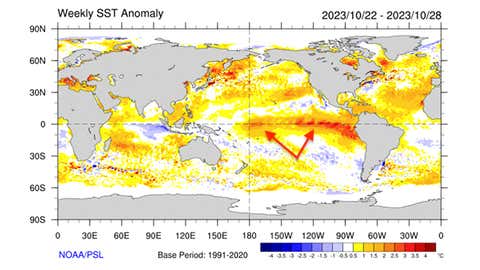

First, what is El Niño and how strong is it? It is a periodic rise in temperatures in the eastern and central tropical Pacific Ocean. This year, the El Niño phenomenon occurred for the first time in June, the first in more than four years.

Since the end of August, warm temperature anomalies have exceeded the threshold for a strong El Niño, by at least 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, which is warmer than average.

Sea surface temperature differs from average (in degrees Celsius) during the last week of October 2023. El Niño is marked with red arrows.

(NOAA/POSL)

What is the importance of this strip of warm ocean water? El Niño and its cold counterpart La Niña can affect weather patterns thousands of miles away in the United States and around the world. Since most El Niños peak in late fall or winter, they can have their strongest impact in the colder months of the year.

In general, classic El Niño winters tend to be wetter than average across much of the southern United States, from parts of California to the Carolinas, partly due to the path of the stronger southern jet stream.

In much of the northern United States, stronger El Niños tend to produce warmer winters.

Boost your forecast further with our detailed hour-by-hour breakdown for the next eight days – only available on our website Premium Pro experience.

Typical impacts during a strong El Niño from December through February in North America.

(NOAA)

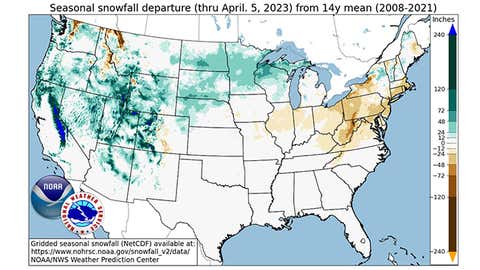

How could snowfall be different this season? Last season was a clear case of the snow haves and have nots. Specifically, much of the west into the northern Plains and upper Midwest was snowier than average. However, much of the Northeast was noticeably less snowy than normal.

The 2022-2023 season begins with below-average snowfall through April 5, 2023. While much of the West to upper Midwest was snowier than average, much of the Northeast had less snow last season.

(Greg Karbin (NOAA/NWS/WPC))

The two main changes in snowfall we may see this season due in part to a stronger El Niño are:

– Less snow: Pacific Northwest, Northern Rockies and upper Midwest.

-More snow: parts of the mid-Atlantic states.

Snowfall varies from average during moderate to strong El Niño periods from January to March. Brown areas typically see less snow, while blue areas typically see more snow.

(NOAA/Climate.gov)

As you can see, this is a pretty broad swath of the northern tier of states that may have less snow this winter.

Particularly interesting is the possibility of a snowier mid-Atlantic region. Last season, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., all failed to collect an inch of total snowfall. One of the most recent stronger El Niños occurred in 2009-2010, which included the infamous twin “Snowmageddon” snowstorms in the mid-Atlantic states in early February.

(More details: How does El Niño affect seasonal snowfall?)

Where can it be wetter or drier? Beyond the snowfall discussion, last season was unusually wet from the Southwest to the upper Midwest, but drier in parts of the Southern Plains and Florida.

Looking back at stronger El Niños in the past, here are two potentially significant changes this season:

- Witter: Florida to Texas.

Driest: parts of the Ohio Valley.

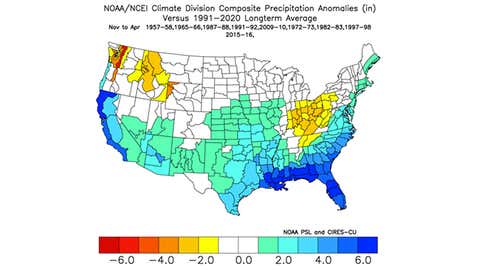

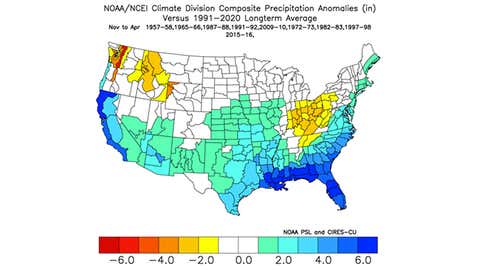

Departures from average precipitation (rain and melting snow) from November to April during the nine strongest El Niño events since 1950.

(NOAA/POSL)

This means Florida's typical dry season could be less than that in 2023-2024. Keep this in mind if you are a snowbird migrating from cold climates and looking for sunshine and a break from the winter cold.

For wetter parts of the South, it could also mean more snow and ice events if there happens to be enough cold air in place when the aforementioned turbocharged southern branch of the jet stream is active.

How could the El Niño phenomenon change temperatures this season? Last season, a stubborn split dominated as the West and Northern Plains continued to cool but overall the rest of the lower 48 states were milder.

There are two potentially significant changes likely this season, if past El Niños are any indication:

- More moderate: Pacific Northwest, Northern Rockies.

– Cold: Most of the south.

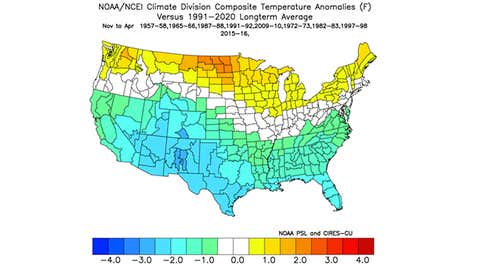

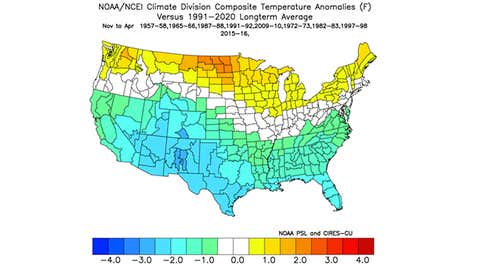

As above, but with variations from average temperatures (rain and melting snow) from November to April during the nine strongest El Niño events since 1950.

(NOAA/POSL)

But the matter is not limited to the El Niño phenomenon only. Now we get to the warnings and asterisks.

First, not all El Niños are exactly the same. Even a stronger El Niño does not necessarily guarantee strong effects on the weather pattern.

Just as the price of gasoline does not control the entire economy, the El Niño phenomenon is not the only factor that affects winter weather.

Other components can overshadow the scenarios we described above.

Greenland bloc

One is the extent to which blocking occurs in the upper levels of the atmosphere near Greenland this winter.

When high pressure forms near Greenland, it blocks the jet stream's west-to-east flow, forcing it to dip sharply south into the eastern United States.

A high-pressure blocking area near Greenland is forced to descend southward in the jet stream across the eastern states when the North Atlantic Oscillation is in its negative phase. This leads to continued cold temperatures and the possibility of snow storms on the East Coast.

Known to meteorologists as the Greenland Block, this pattern delivers abundant cold air from Canada and is an instigator of blizzards on the East Coast.

How often this pattern will develop in any given winter is difficult to predict months in advance.

But if the Greenland Block forms more frequently during stronger El Niño winters, parts of the southeast and mid-Atlantic could see colder and snowier winters. This occurred during the strong El Niño of 2009-2010, which caused winter cold to spread much more widely than the typical strong El Niño discussed earlier.

Polar vortex

Another winter factor that is difficult to predict months in advance is the polar vortex, a swirling cone of low pressure above the poles that is strongest in the winter months.

When the polar vortex weakens, cold air normally confined to the Arctic can spread to parts of Canada, the United States, Asia and Europe as the jet stream becomes more obstructed by steep southward swerves, sending more persistent cold air south toward the mid-Arctic. -latitudes.

One such event triggered a historic cold snap in February 2021 that paralyzed parts of the Plains, outpacing the overall warm winter typically seen in the South during La Niña.

An example of a weak polar vortex in winter.

A stronger El Niño gives us more confidence that it will have an impact during the colder months ahead. Time will tell how much these other factors will cloud this picture.

Jonathan Erdmann is a senior meteorologist for Weather.com and has been covering national and international weather since 1996. His lifelong love of meteorology began with a close encounter with a tornado as a child in Wisconsin. He studied physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then completed a master's degree working with dual polarization radar and lightning data at Colorado State University. Extreme and strange weather are his favorite subjects. Contact him on X (formerly Twitter), Threads And Facebook.

The Weather Company's primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment, and the importance of science in our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.