- The strong El Niño phenomenon is expected to remain in place through the spring.

- The last two strong El Niño winters were very different.

- This is because El Niño is not the only driver of weather patterns.

- Initial evidence suggests that this El Niño winter bears some similarities to one of those past events.

El Niño is getting stronger, but the last two U.S. winters with strong El Niño events were different in several key ways, adding uncertainty to this season's forecast.

What is the El Niño phenomenon? It is a periodic rise in temperatures in the eastern and central tropical Pacific Ocean. This year's El Niño began developing in June, becoming the first in more than four years.

Since the end of August, warm temperature anomalies have exceeded the threshold for a strong El Niño, by at least 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, which is warmer than average. It's the first time this has happened in more than seven years.

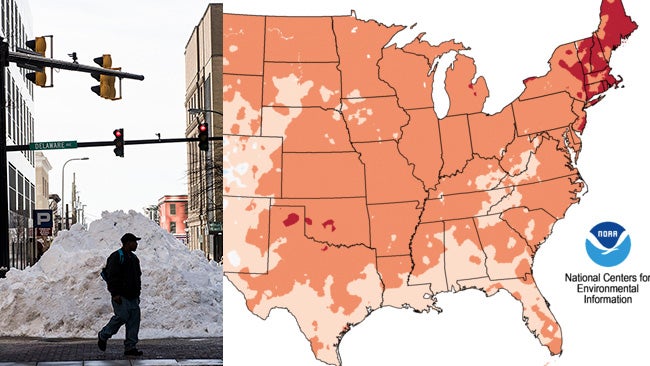

Sea surface temperature differs from average (in degrees Celsius) during the last week of October 2023. El Niño is marked with red arrows.

(NOAA/POSL)

What is the importance of this strip of warm ocean water? El Niño and its cold counterpart La Niña can affect weather patterns thousands of miles away in the United States and around the world. Since most El Niños peak in late fall or winter, they can have their strongest impact in the colder months of the year.

In general, classic El Niño winters tend to be wetter than average across much of the southern United States, from parts of California to the Carolinas, partly due to the path of the stronger southern jet stream.

In much of the northern United States, stronger El Niños tend to produce warmer winters.

Boost your forecast further with our detailed hour-by-hour breakdown for the next eight days – only available on our website Premium Pro experience.

Typical impacts during a strong El Niño from December through February in North America.

(NOAA)

Not all El Niños are exactly the same. Even a stronger El Niño does not necessarily guarantee strong effects on the weather pattern as we discussed above. It's not the only factor that affects winter weather. The latest strong El Niño winter confirms this fact.

2015-16

El Niño was already strong by late summer, and eventually topped out as one of the strongest El Niño on record by that winter.

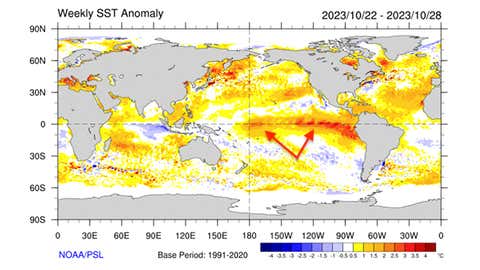

It was, and continues to be, the warmest winter on record in the United States In general, stronger El Niños generate mild winters in most parts of the country.

2015-16 did so on a large scale. This was the country's warmest winter on records dating back to 1895, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It was record warm in every New England state, plus New York City, despite a brief cold outbreak in the Northeast on Valentine's Day. It even rose to the 70s in late February in North Dakota.

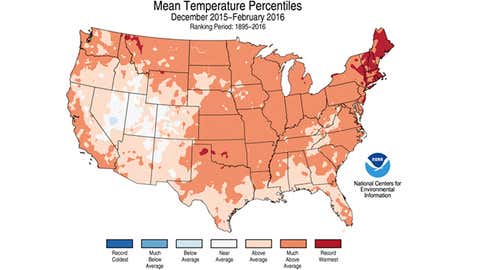

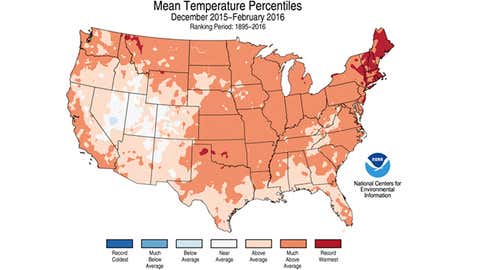

Temperature percentiles for December 2015 to February 2016, compared to other December-February periods since 1895. Areas in dark red were record warm in 2015-2016.

(NOAA)

But it caused a huge storm on the East Coast. Despite all that warmth, there was enough cold air before a powerful jet stream to grab a massive snowstorm in parts of the Northeast in late January 2016.

Winter Storm Jonas was New York City's heaviest snowstorm on record (27.5 inches), as well as in Baltimore, Allentown, and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimated that 21 million people caught at least 20 inches of snow from Jonas.

Eleven states and the District of Columbia have declared states of emergency, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Travel bans were issued in New York City and Newark, and more than 13,000 flights were cancelled.

This is despite New York City and Philadelphia waiting until January for their first snow accumulation. Even a record mild winter can generate one or more major winter storms.

Morning commuters pass through plowed snow on Wall Street in front of Federal Hall in New York's Financial District, Monday, January 25, 2016. East Coast residents who made the most of a weekend snowstorm face new challenges as the work week begins: slippery roads, spotty transit service and pile-ups. From the snow buried cars and blocked the entrances to the sidewalks.

(AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Rainy areas fit the model. The 2015-16 season was the wettest winter on record in parts of the Southeast, including Atlanta and Miami, and in Iowa, as well as in parts of the Pacific Northwest, including Seattle. This fits the typical stronger El Niño picture for the wetter Gulf Coast and Florida.

This wet, southern scenario continued into the spring, leading to major flooding along the Sabine River in Texas and Louisiana in March, Tax Day flooding in Houston, and then another flood of metro Houston in May.

Locations in the contiguous United States that recorded either a record or second wet season from December to February in 2015-2016. (Note: Only sites with data at least 60 years old are included.)

(Data: NWS, SERCC)

2009-2010

This El Niño phenomenon had almost no development in early 2015-2016 or in the current period, and had barely reached strong territory by winter.

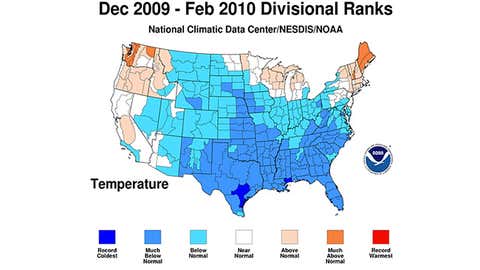

It was the country's coldest winter this century. Considering what we have set for 2015-2016, this seems shocking, doesn't it? Most of the lower 48 states had persistent cold from December 2009 through February 2010, despite a strong late El Niño.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), nearly every Southern state has experienced one of the 10 coldest winters, from South Carolina to Florida to Texas. Overall, this was the country's coldest winter since 1984-85, and still ranks among the top 25 coldest winters on record.

But there are still some warm pockets, including parts of the Great Lakes, Northeast, and Northwest. Maine experienced its third warmest winter at that time.

Temperature percentiles from December 2009 through February 2010, compared to other December and February periods since 1895.

(NOAA/NCEI)

The mid-Atlantic was buried in historic snow. The winter of 2009-2010 rewrote snowfall records in parts of the East.

This was the snowiest season (fall to spring) on record in Baltimore (77 inches), Philadelphia (78.7 inches), and Washington, D.C. (56.1 inches). February 2010 was the snowiest month since 1869 in New York City (36.9 inches) and Pittsburgh (48.7 inches).

This was primarily due to several large winter storms. One happened just before Christmas. Two more incidents occurred within a week in early February. Dubbed “Snowmageddon” and “Snowmageddon II,” they dropped a combined 44 inches of snow in both Baltimore and Philadelphia, and nearly 29 inches in Washington, D.C. Hundreds of thousands were without power and some roofs collapsed.

Left: A high-resolution visible satellite image showing the extensive snow cover over the mid-Atlantic on February 8, 2010, after the first “Snowmageddon” snowstorm. Right: A Capitol Architect removes snow using a front-end crane on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol, February 11, 2010, in Washington, D.C.

(Left: NASA Worldview; Right: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Why was a strong El Niño winter so different? Although the winter of 2009-2010 had some small signs of a stronger El Niño winter, another factor overshadowed the El Niño effect: Greenland's mass.

It is an area of high pressure in the upper levels of the atmosphere near Greenland. When this forms, it blocks the jet stream's west-to-east flow, forcing it to take a sharp southerly direction toward the eastern United States.

When it happens in the winter, this pattern transports cold air from Canada to the central, southern and eastern United States, and can also open the door to one or more snow storms on the East Coast.

A high-pressure blocking area near Greenland is forced to descend southward in the jet stream across the eastern states when the North Atlantic Oscillation is in its negative phase. This leads to continued cold temperatures and the possibility of snow storms on the East Coast.

One way meteorologists track this blocking pattern is through an indicator called the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). A more negative NAO means more blocking in Greenland, while a more positive NAO means there is less blocking near Greenland.

This shows the main difference between the two best El Niño winters.

In the winter of 2009-10, Greenland's blocking was prevalent, with a sharp decline in the value of net exports as the chart below shows.

However, the winter of 2015-2016 had mainly positive NAO values, indicating little blocking in Greenland. In this case, the cold air tended to drain more often eastward across eastern Canada, rather than diving into the United States.

North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index from 2009 through summer 2016. Greenland occultation times (negative NAO) are shown by red bars. Lower Greenland blocking (positive NAO) is shown by blue bars. Time frames are shown for the winters of 2009-2010 and 2015-2016.

(NOAA/NCEI)

What are your takeaways for this winter? How often a block pattern will develop in Greenland in any given winter season is difficult to predict months in advance.

There are also other unexpected factors, such as a weakening polar vortex, which could also lead to a colder, more stuffy pattern for some time this winter.

There is preliminary evidence that the influence of El Niño on the large-scale weather pattern in the Pacific region began more in the period 2009-2010 than in the period 2015-2016.

A stronger El Niño gives us more confidence that it will have some impact during the colder months ahead. Time will tell how much these other factors will cloud this picture.

Jonathan Erdmann is a senior meteorologist for Weather.com and has been covering national and international weather since 1996. His lifelong love of meteorology began with a close encounter with a tornado as a child in Wisconsin. He studied physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then completed a master's degree working with dual polarization radar and lightning data at Colorado State University. Extreme and strange weather are his favorite subjects. Contact him on X (formerly Twitter), Threads And Facebook.

The Weather Company's primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment, and the importance of science in our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.