Mr. Ozawa, who underwent treatment for esophageal cancer in 2010, had been in fragile health for years. He was expected to perform with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in July 2016, but withdrew in May of that year due to what was described as a “lack of physical strength.”

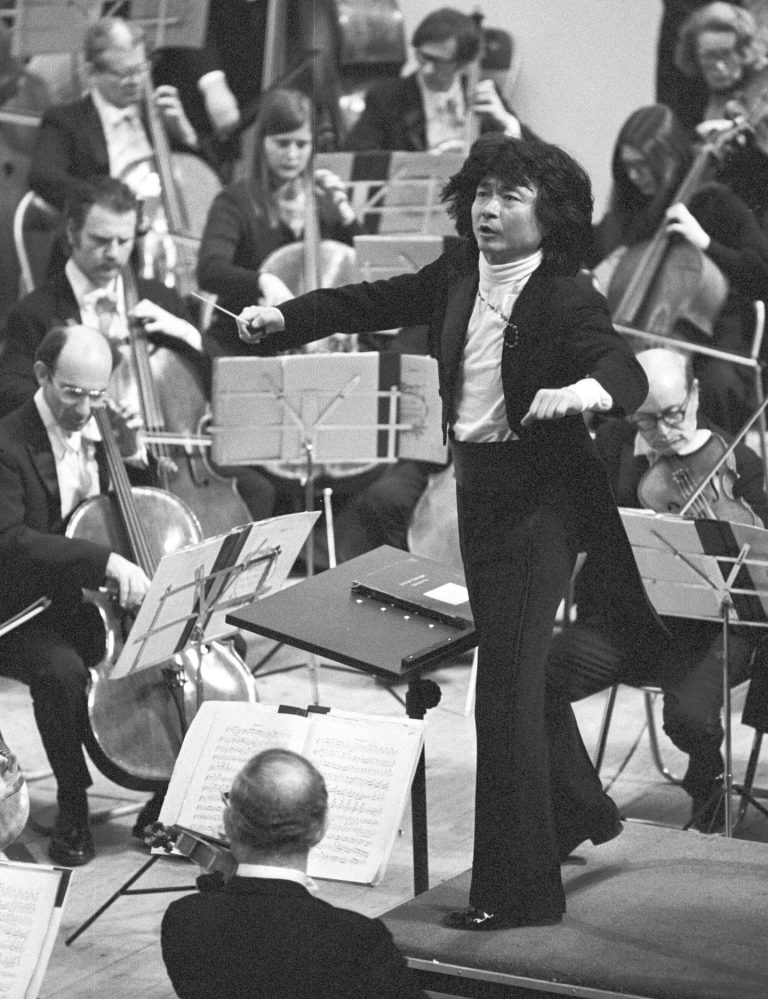

It was a sad end for a man who arrived in Boston in the early 1970s as a long-haired, fashionably dressed conductor who exuded youthful energy. He seemed in stark contrast to the middle-aged, tuxedo-clad Northern Europeans who had long dominated the podium in classical music.

It was the fall of the counterculture, Boston was booming, and Mr. Ozawa seemed at home in most college towns, newly awakened from a long period of being considered staid and isolated. His elaborate, turtle-necked, love-embroidered image (brilliantly developed by the BSO's public relations department) made him seem like a new kind of music director for a new age.

Suddenly, Mr. Ozawa was everywhere: leading the BSO as well as the Muppets' all-animal orchestra on public television, gracing the covers of magazines, and appearing at Red Sox games as a high-profile ticket holder. He won two Emmy Awards for his televised performance and was the subject of a documentary co-directed by the Maysles Brothers.

Ozawa joined a small group of classical musicians, including Beverly Sills, Leonard Bernstein, and Luciano Pavarotti, who were known not only to concert audiences, but also to the general public.

Despite the publicity blitz, it was clear from the beginning that Mr. Ozawa was a serious, thoughtful and prodigiously talented musician. He dazzled orchestras and audiences with what Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Leon Kirchner once called “the scent, feel, and sensuality of an extraordinary person.” He attracted world-class mentors such as Bernstein of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and Herbert von Karajan of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

Richard Dyer, a longtime Boston Globe music critic, wrote in 2002 that Mr. Ozawa “displayed the greatest physical talent for conducting of anyone of his generation, and a range and precision of musical memory that struck awe and envy in the hearts of most musicians.” Who confronted him?

In later years, Dyer added, he remained “beautiful to watch, and unique in the amount of concentrated information and emotion he could communicate through look, posture and gesture.” Ozawa is the moving, precise and evocative line.

Mr. Ozawa had an almost unparalleled talent for uniting massive orchestras and choirs in long, complex, densely populated works, such as Hector Berlioz's “Damnation de Faust,” Arnold Schoenberg's “Gurre-Lieder,” Benjamin Britten's “War Requiem,” and War Requiem by Richard Strauss. The opera “Electra” which he performed in concert with the BSO.

He conducted the world premiere of Olivier Messiaen's 4½-hour opera Saint François d'Assis (1983) at the Paris Opera. The score called for a 150-strong orchestra and included 41 parts for percussion alone.

He recorded all of these works, as well as complete symphonies by Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Gustav Mahler, and hundreds of other scores. Most of his discs have been made with the BSO, but he has also recorded with leading orchestras including Vienna and Tokyo.

But his tenure in Boston—at 29 years, the longest as music director in the orchestra's history—is likely to be his main legacy. It was a legacy that became hotly debated over the years. As his commitments mounted, many critics expressed dismay that Ozawa, once so cheerful, seemed to increasingly resort to routine and often artistically ill-considered performances. Morale among musicians declined.

He retained loyal fans and protectors who continued to bestow laurels on him, and he received a 2015 Kennedy Center Honoree, which described him as “one of the great figures in the world of classical music today.” But there was relief when James Levine, the Metropolitan Opera's longtime music director, took over for Mr. Ozawa's duties at the BSO.

At first, it looked as if Levine was beginning to re-energize the BSO before his health setbacks interfered with his demanding schedule and he began canceling many of his appearances. Levin left in 2011 in what was presented as a “mutual decision.”

Seiji Ozawa, the third of four siblings to a Buddhist father and a Christian mother, was born on September 1, 1935, in Mukden (now Shenyang), Manchuria, during the Japanese occupation of that region of China.

His father was there as a dentist for the railway company, but his growing sympathy for the plight of the Chinese and his involvement with a pacifist organization led to conflicts. The Ozawa family was soon deported to the Japanese mainland.

His family settled in Tachikawa, the site of a military air base outside Tokyo. His father was denied a license to practice as a rice farmer. Mr. Ozawa vividly remembers being drawn to music by the church hymns his mother would sing around the house.

He soon began keyboard studies, immersing himself in Brahms, Beethoven and Johann Sebastian Bach with the aim of becoming a concert pianist, an ambition he abandoned in his teens after breaking his index fingers playing rugby.

After his piano teacher asked him to consider conducting the band, he went to hear a live symphony for the first time. Ozawa, then 14, said he found the show a revelation: not the soft noise of an old radio or record player, but a vortex of movement and force that sent shivers down his spine.

As Mr. Ozawa recalls, his mother then wrote a letter to a distant relative, the cellist, conductor and teacher Hideo Saito, who was influential in introducing Western classical music to Japan and especially to Japanese children.

Mr. Ozawa paid for his lessons at the Saito Toho Gakuen Music School in Tokyo by helping with orchestration and mowing the lawn. Emerging as a brilliant student, he set out in 1959 to compete in an international competition for young conductors in Besançon, France, and made a two-month voyage to Europe on a cargo ship.

It won first place in Besançon and particularly impressed one of the judges, Charles Monk, music director of the Boston Symphony. Monk invited him to attend the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood, the summer home of the BSO in western Massachusetts, which was founded in 1940 to promote young instrumentalists and composers.

Mr. Ozawa received Tanglewood's highest conducting honor in the summer of 1960, and Bernstein appointed him assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic beginning in the 1961-62 season.

Bernstein's influence on Mr. Ozawa was significant, not only in the physicality of their style from the catwalk but also in their preference for fashionable clothes and their similarly unruly hair, which they liked to sweep back by hand in the middle of a particularly powerful performance.

Such habits did little to endear Ozawa to his compatriots when he returned to Japan in 1962 to conduct the country's leading ensemble, the NHK Symphony Orchestra. Some older musicians refused to play with him, as they found his style too arrogant and Western.

“For a Japanese person, my talent matured too quickly,” he told the Globe years later. “I came to prominence the way kernels quickly turn into popcorn. Orchestra members boycotted me. They said I had bad manners. It was true. They said I pressured them too hard. It was true. They said I was a bully. It was true. I thought it was “It was just a matter of working hard. But the management was on the musicians' side.”

However, Mr. Ozawa kept returning to Japan for engagements while quickly making his name in North America.

At the age of twenty-eight, he became music director for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra's summer season at the Ravinia Festival. In addition, he was appointed permanent conductor of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in 1965 and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in 1970. Boston then brought the opportunity to assume leadership of one of the oldest and most prestigious orchestras in the United States.

He became music advisor to the BSO in 1972 and music director the following year. By the end of the decade, as Communist China began to re-establish cultural ties with the West, he accepted an invitation to conduct the Central Beijing Philharmonic Orchestra in China. He also took the BSO on tour in China, the first Western orchestra to undertake such an adventure.

In an agonizing decision made in the late 1970s, Mr. Ozawa and his second wife, Vera Elian, of Russian and Japanese descent, decided to return to Tokyo and raise their two children there, immersing them in the Japanese language and cultural values. .

Yet he continued to add to his duties. In 1992, he founded the Saito Kinen Festival in Matsumoto, Japan, naming what immediately became one of the world's leading youth orchestras in honor of his mentor. As is customary with BSO music directors, he also served as director of the Tanglewood Music Festival and, in 1994, opened the Seiji Ozawa Hall on its western grounds. Most of the funding came from Sony: Mr. Ozawa was now a national hero in Japan.

In 1997, Mr. Ozawa became a controversial figure at Tanglewood when he fired a popular principal, Richard Ortner, over conflicts over student programming and coaching. Several famous faculty members—among them pianists Leon Fleischer and Gilbert Kalish and bassist Julius Levin—left in protest.

Moreover, relations with the orchestra were strained by the traveling workload, and what had once seemed a magical connection to the orchestra seemed increasingly archaic. The critical consensus was that he stuck around for the long haul. “He still dances on the platform with his signature charm, but he sounds much better than his orchestra sounds,” composer and critic Greg Sandow said in the Wall Street Journal.

Mr. Ozawa resigned from the BSO in 2002 to become music director of the Vienna State Opera, a position he held for eight years.

He and Elian had two children. His first marriage to pianist Kyoko Ido ended in divorce. A list of survivors was not immediately available.

Mr. Ozawa holds dual Japanese-American citizenship, and described his life and career as a successful, if not always entirely seamless, blend of Eastern and Western culture and pride. “Western music is like the sun,” he told Time magazine in 1987. “All over the world, the sunsets are different, but the beauty is the same.”