Chosen by Alexander Lisle

Ukrainian artist Dana Kavilina revives traditional animation techniques – puppetry, stop motion, drawing on paper, costume parties, and model kits – in order to consider future techniques. Bodies, war, and historical atrocities. Takes Limberg machine (2023), a stop-motion animated film loosely based on the Lviv pogroms of 1941. Kavelina built a set of miniature model kits to film a series of vignettes that follow a group of puppet characters. All accompanying dialogue is in Russian or Yiddish (with English subtitles). In one scene, a woman plunges into a burning pyre—her body does not catch fire, but silently disappears in the dancing flames of worn-out orange and red cotton; A German Einsatz soldier fires his rifle into the air and parts of the dusk backdrop, like curtains, to reveal the starry night sky, while other soldiers clap, whistle and scream. This tug of war between melancholy beauty, horror and absurdity is a feature of Cavilina's work.

The viewer must also know his role, as Cavelina links the role of witness to that of perpetrator: “The camera and the torture chamber intertwined and fell one by one,” the narrator tells us ambiguously later in the novel. film; Or in another job Message to the turtle (2020), which combines drawn and drawn photographs with found documentary footage, we can sometimes see a nude figure looking directly into the lens, eyes staring upward through a broken pane of glass. In Kyiv it opened Room of Yulia Efremova (2020), in which she created the living space of a fictional artist who committed suicide, as diaries and letters indicate. Only one visitor is allowed at a time, for an unlimited period; So waiting was part of the work experience. Once inside, the space was entirely yours to take in: artwork, poems, photos, a laptop, and clothes on the railing. How can we, as visitors in this constructed position of voyeuristic power, think about the spectacle of suffering? Elsewhere, though, her sometimes dry, tongue-in-cheek sense of humor is refreshing: in a scene from the film There are no traces of antiquities (2021), the artist bends, suspended at the waist, resting her head between the limbs of a political statue frozen in a triumphant wave; “It's very rocky,” the narrator comments in mockumentary style, “probably rockier than average.”

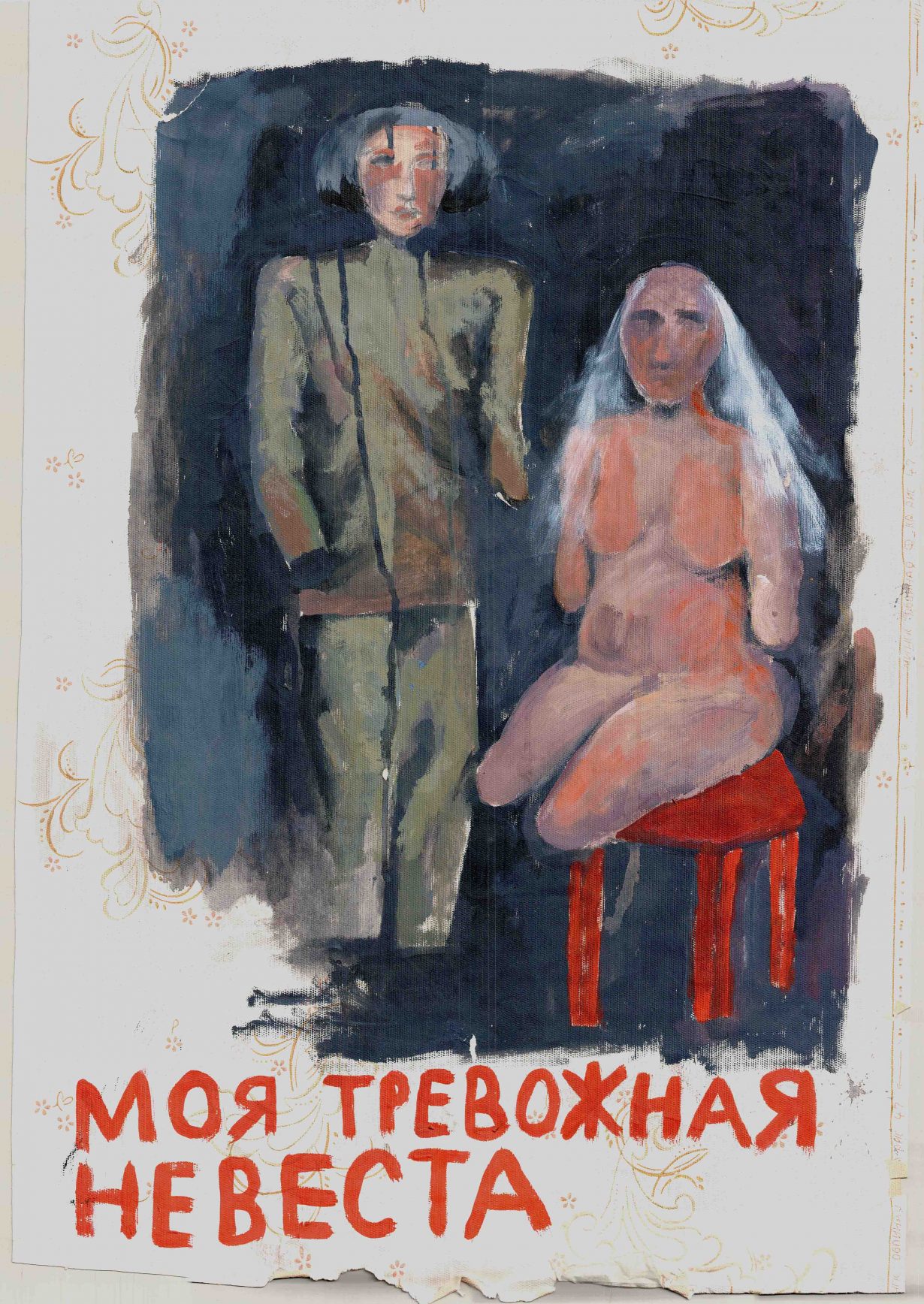

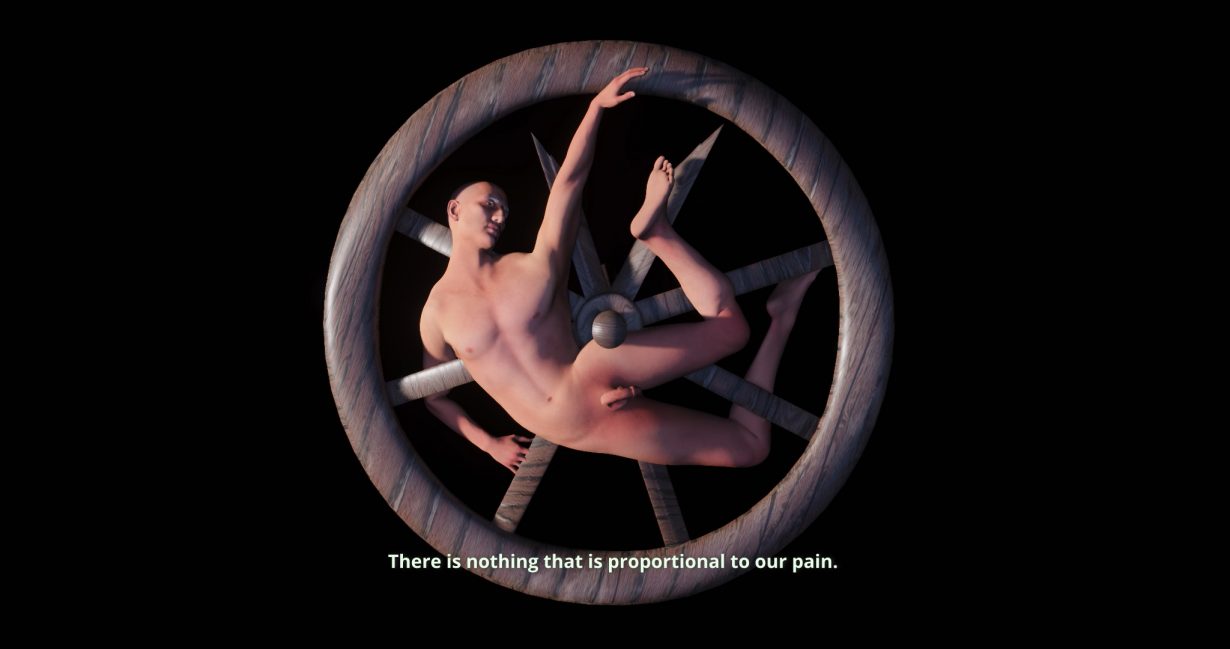

Cavelina's practice is decidedly community-based, and she raises the level of presentation of her video works by presenting photographs, prints and artefacts saved from the production phase of the work on walls and in vitrines. A similar attitude applies to her films, which she often screens and then later edits, suggesting, along the way, that there is no such thing as a “finished” work. One of these “unfinished business”, There can be nothing that can be returned (2022), indicating her ambition to continue working with digitally modeled images. In one scene, a voiceover in the form of an advertisement tries to sell us on a utopian vision: Ukraine has won the war against Russia in 2022; It is now a borderless country defined by its cities and governed by an artificial intelligence modeled on Soviet cyberneticist Viktor Glushkov. The editing here is both exhilarating and disturbing: “The trees migrate… The street wants to come out and become an animal… Sometimes everything suddenly dances.” We explore the locations of this bizarre fantasy: there is a pile of eyeballs, each individually frozen in glass cubes, on a factory conveyor belt; Military heat-vision clips—of insects feeding, pigs sleeping in their pen, drone shots of urban society—melt together like a frenetic film reel. This is the vitality of Cavilina's work: a tangible, almost spiritual concern for the coexistence of ideas, bodies and technologies in a world where the worst has already happened.

Dana Kavelina works in animation, video, installation, drawing and graphics. She graduated from the Graphics Department of the National Technical University of Ukraine in Kiev, and now resides in Berlin. Her feature film This cannot be anything that can be returned (2022) was screened at the BFI London Film Festival in 2023.

Alexander Lisle is Assistant digital editor Art review.