His son, Sam Pilger, said the cause was pulmonary fibrosis.

In columns, articles, books and television documentaries, Mr. Pilger has campaigned to expose government malfeasance and corruption, and has traveled the world reporting on the Vietnam War, the “killing fields” of Cambodia, the Troubles in Northern Ireland and expelled Palestinians in Cambodia. Gaza and the West Bank. His work brought him a large number of journalistic awards as well as scorn and ridicule, with critics saying he was less a reporter than a polemicist, driven by the belief that Western governments were responsible for some of the worst human rights abuses of the 20th century.

Mr. Pilger, an Australian citizen who has been based in Britain for most of his career, was quick to distance himself from most reporters in the mainstream media, whom he saw as shorthand for the rich and powerful.

“It is not enough for journalists to see themselves as mere messengers, without understanding the hidden agendas of the message and the myths that surround it,” he wrote in 1998. “At the top of the list is the myth that we now live in an ‘Information Age’ world – when in reality we live in a media age, where available information is repetitive, ‘secure’ and limited by invisible borders.

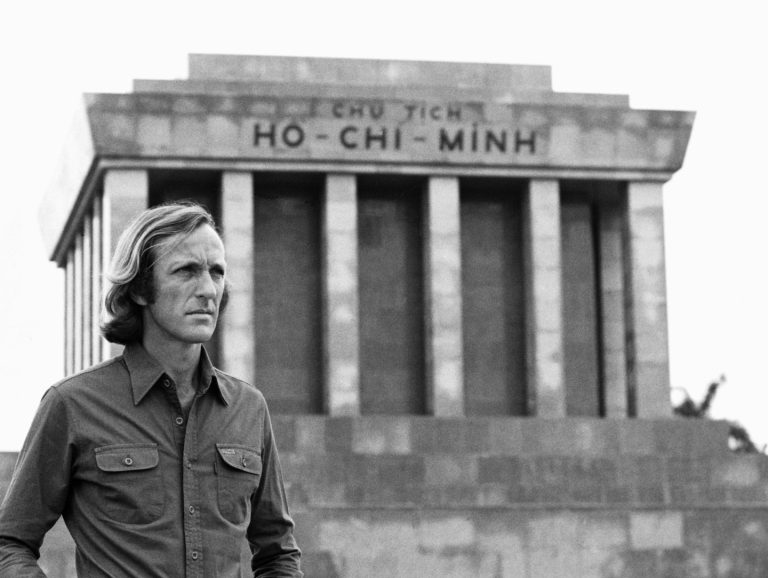

Mr. Pilger (pronounced PILL-jer) was just 27, and serving as the Daily Mirror's chief foreign correspondent, when he was honored at the British Press Awards as Journalist of the Year for 1967, for his correspondence from the Vietnam War. He was honored with the award for a second time for his 1979 report on the Khmer Rouge, the communist regime that ruled Cambodia for four years under dictator Pol Pot.

Other reporters, including Elizabeth Baker of the Washington Post and Sidney H. Schanberg of the New York Times, covered the brutality of the dictatorship. But Mr. Pilger has been widely credited with helping to draw broader attention to the genocide in Cambodia, which claimed the lives of an estimated two million people, nearly a quarter of the country's population.

Mr Pilger said he wanted to “put Cambodia back on the human map” through his reporting, which included articles in the Mirror – an entire issue of the paper was devoted to his work – and a documentary called “Year Zero: The Silent Death”. Cambodia” (1979) directed by his friend David Munro. The documentary was filmed in Cambodia shortly after Vietnamese forces ousted the Khmer Rouge from power, and included interviews with survivors, including two artists who were among the only members of a group of 12,000 people Who survived because they made attractive busts and paintings of Pol Pot. Mass murder, forced labour, famine and disease.

The film reportedly raised more than $45 million in aid for Cambodia, including millions of dollars in small donations raised by British school children.

Mr. Pilger and Monroe later collaborated on documentaries including “Death of a Nation” (1994), about Indonesia's invasion of East Timor in 1975 and the bloody occupation that followed. The filmmakers arrived in East Timor secretly, posing as travel company officials, and used small video cameras to document the aftermath of attacks across the island, including the massacre of up to 200 pro-independence protesters in a cemetery in Dili, the capital. .

To peers such as Martha Gellhorn, the famous American war correspondent, Mr. Pilger was “a courageous and invaluable witness to his time.” His journalism brought him numerous honors, including a Peabody Award, for the documentary Cambodia: Year 10 (1989), about the legacy of the Khmer Rouge; and the International Emmy Award for “Cambodia: Betrayal” (1990), about fears of Pol Pot and his allies returning to power; and the 2009 Sydney Peace Prize, for “Enabling the voices of vulnerable people to be heard.”

However, critics said Mr. Pilger's work was more often filled with righteous anger than rational analysis, and said that for all his criticism of Western powers, he tended to overlook abuses by repressive leaders such as Hugo Chavez in Venezuela and Vladimir Putin in Russia. . Many critics objected to the blame he attributed for the genocide in Cambodia, much of which he placed at the feet of American leaders who authorized the bombing of the country during the Vietnam War.

“The Holocaust in Cambodia was as much the work of America as it was the work of Pol Pot,” he wrote in a 1990 article for The Guardian. British journalist William Shawcross, who worked as a correspondent in Cambodia, wrote in an article for the Observer that this comment represented a case of “moral relativism gone mad.”

“Pilger often subverts his case by insisting on his monopoly on wisdom, by abusing those who disagree with him, by dealing with emotions as much as facts, and by seeing everything through the lens of distorted anti-Americanism,” Shawcross said. .

Mr Pilger's journalistic reputation has been damaged by a number of high-profile missteps, including a 1991 libel case in which he was found to have defamed two former British soldiers through one of his documentaries in Cambodia, in which he claimed the two men were training Khmers. Red gangs for planting landmines. The London Evening Standard reported that Mr Pilger had never met the two men and had not “tried to talk” until he met them in court. He agreed to apologize and retract, and each of the men was said to receive compensation of around £100,000.

The libel case followed a disastrous 1982 Daily Mirror article written by Mr Pilger about child slavery in Thailand, in which he reported that he had bought an enslaved eight-year-old girl called Sunny – at a cost of £85 – and then reunited her. With her mother in a village outside Bangkok. The story gained international attention and was quickly shown to be untrue: the Far East Economic Review reported that Mr. Pilger hired an intermediary, a local taxi driver, to help with the story, and found that the enterprising driver had located a schoolgirl. Bangkok paid her family to play the trick.

Mr Pilger claimed that attempts to distort the story were “exaggerated, spiteful and cowardly”. He later said the repairman had tricked him. The case prompted Auberon Waugh, the journalist and satirist, to coin a new verb: “to pilger”, which he jokingly defined as “endeavoring to arouse indignation by exaggerated or absurd propositions” or “to smear in a prejudiced manner”. “.

The term was made into a reference book, the Oxford Dictionary of Neologisms, only for the editors to announce in 1994 that it would be withdrawn from subsequent editions after complaints from Mr Pilger.

By then, some of his admirers had sought to reclaim the term. Journalist Philip Knightley wrote for the Spectator magazine to offer his own definition: “The verb ‘to argue’,” he declared, “means to look with insight, compassion, and sympathy.”

John Richard Pilger was born in Bondi, a suburb of Sydney, on 9 October 1939. His mother was a teacher, and his father was a carpenter and trade unionist.

Mr Pilger started a student newspaper at his Sydney high school, and completed a four-year journalism apprenticeship with Australian Consolidated Press. He wrote for the Daily and Sunday Telegraph in Sydney, briefly tried freelance work in Italy and moved to London in 1962, where he worked for Reuters before joining the Daily Mirror as a reporter in 1963, just as the tabloid was expanding its coverage of national and foreign affairs. .

Within a few years, he was reporting abroad. He had come to the United States to report on civil rights and was at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles the night that presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, a U.S. senator and former attorney general, was shot to death.

Mr Pilger began working on documentaries in the 1970s, covering topics including the devastating effects of thalidomide, a drug once widely used and marketed to pregnant women, and the history of Indigenous Australians. He was sacked from the Daily Mirror in the mid-1980s, after falling out with new publisher Robert Maxwell, and later worked as a columnist for the New Statesman.

His marriage to Scarth Fleet ended in divorce. In addition to his son Sam, a sportswriter, survivors include Mr. Pilger's partner of more than 30 years, Jane Hill; daughter of novelist and art critic Zoe Pilger, from a relationship with journalist Yvonne Roberts; and two grandchildren.

Late in his life, Mr. Pilger campaigned for the release of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who is fighting extradition from Britain to the United States and charged under the Espionage Act. “If Julian Assange is extradited to the United States, the idea of a free press will be lost,” he told The Independent in 2021. “No journalist who dares to challenge greedy power and expose the truth will be safe.”