US officials describe the approximately 2,500 soldiers in Iraq and 900 soldiers in Syria as part of an operation to prevent ISIS from regaining a foothold in the region. But with the jihadist organization largely in decline, American soldiers now find themselves targeted by other adversaries, who say attacks will continue as long as Washington maintains its support for Israel's war in Gaza.

Locations of all 165 attacks on the United States

Forces since the beginning of the war between Israel and Gaza

Attacks from October 17 to January 29

Source: US Department of Defense

Samuel Granados/The Washington Post

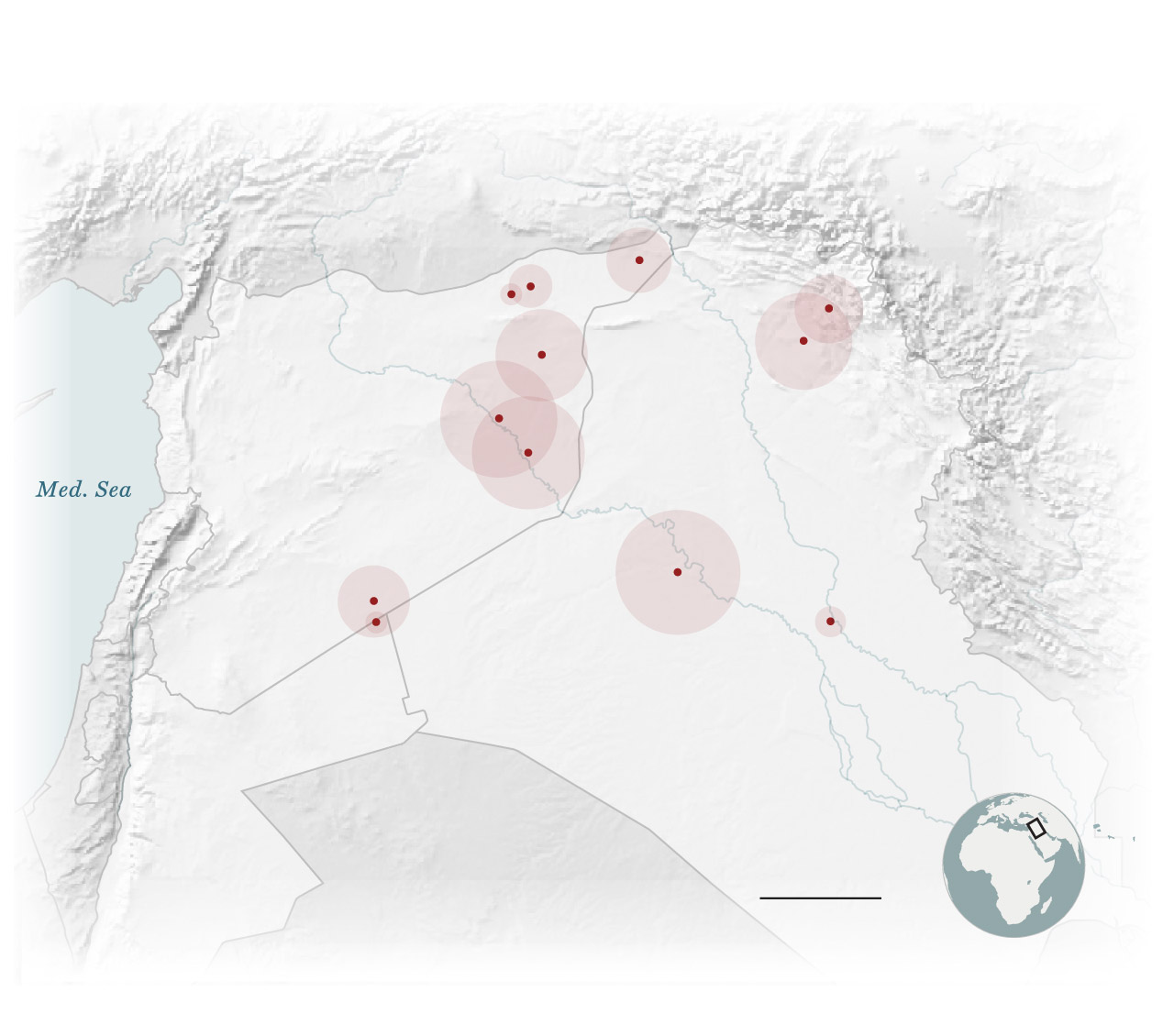

Locations of all 165 attacks on US forces since the start of the war between Israel and Gaza

Attacks from October 17 to January 29

Source: US Department of Defense

Samuel Granados/The Washington Post

“What has happened in the past few weeks has exposed their weakness,” said Darine Khalifa, a senior adviser at the International Crisis Group. “I hope this raises questions about why they are at risk, and how they can make their presence less of a liability for anyone else who works with them.”

The United States had nearly 3,000 troops in Jordan as of 2023, according to the Congressional Research Service, with a focus on Jordanian security and the Islamic State. Officials said Monday that the drone that approached Tower 22, a base in the country's northeast, was mistaken for a returning American plane.

Across the Middle East, US forces have been targeted more than 160 times by Iran-allied militants since October.

The US presence in Syria and Iraq dates back to 2014, when a global coalition joined with local forces to expel Islamic State fighters from a swath of territory the size of Great Britain. Tower 22 in Jordan, an American outpost along the border where the three countries meet, houses about 350 American engineering, aviation, logistics and security personnel, largely providing support to forces in Syria.

Nearly a decade after American soldiers were first deployed, and five years after ISIS was declared defeated, Biden becomes the third president to oversee the mission. But the environment in which it operates has changed radically. The jihadist group now resembles a low-level insurgency, mostly in Syria, rather than a ruling force.

ISIS no longer controls territory in Iraq, and the presence of US forces there has become increasingly controversial among Iraqis, 20 years after the US-led invasion of the country led to a bloody civil war. Although the US military maintains a mandate to advise Iraqi forces, the forces mostly remain at their bases.

US retaliatory strikes on Iran-linked targets inside Iraq, including the 2020 assassination of Tehran's most influential general, Qasem Soleimani, have increased domestic pressure to force America out. Iran's influence in the region has increased as Washington's influence has declined.

The two camps have coexisted uncomfortably for years. Iranian-backed armed groups increased in wealth and power as they led their own battles against ISIS, and some were later integrated into the Iraqi armed forces. Tensions between the militias and American forces escalated in 2018, after President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the historic nuclear agreement that led to a diplomatic opening with Tehran.

Jonathan Lord, the center's director, said the slow pace of change in the US military operation in Iraq is due in part to “a degree of malaise, as well as a cultural and political aversion to risk that is comfortable for the Iraqis and for us.” Middle East Security Program at the Center for a New American Security.

“But that's how you end up having 20-year missions in foreign countries that ultimately don't evolve with the circumstances, and then politics demanding that the mission be finished, even when you don't have permanent, sustainable solutions,” he added. .

When the United States announced a formal end to combat missions in Iraq in 2021, Western and Iraqi officials described the move as more about political optics than changing facts on the ground. Last week, the Biden administration announced that it would resume talks with its Iraqi counterparts about the future of American forces there, in what appears to be the most serious attempt of his presidency to rethink the American military footprint in the region.

American officials seek to separate the talks with Iraq from the turmoil sweeping the Middle East, noting that they resulted from diplomatic efforts dating back several years. “It is not a timeline-driven event,” a senior US military official told reporters last week, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive talks. “We will govern this process through our dialogue together.”

But the continuing attacks on American forces and American military retaliation, especially in Iraq, may also lead to confusion.

“If the frequency and intensity of these attacks increases, it will be difficult to say: OK, let's do this in a measured way, because there will be more pressure, both domestically in the United States and inside Iraq,” one senior official said. A congressional aide has been briefed on the ongoing talks. He spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive negotiations.

The US military footprint in Syria may be smaller, but the politics of withdrawal are more complex.

The 12-year civil war has divided the country into areas of control – the US partners with the Kurdish-led forces, the Syrian Democratic Forces, in the country's northeast; A Turkish-backed authority runs the northwest; The government of President Bashar al-Assad, along with its Russian and Iranian allies, controls much of the rest of the country, including part of the central Syrian desert where ISIS maintains a foothold.

As ISIS has been defeated, other warring parties have claimed territory they previously controlled, hoping to deepen their influence and advance their agendas. American officials believe that Iran's strategic goal is to establish a land corridor between the East and the West linking it with its armed allies in Iraq and Lebanon, and that the American presence in Al-Tanf – an American garrison along the Syrian border with Iraq – stands in the way.

The senior US military official also pointed to the weakness of prisons holding thousands of Islamic State prisoners and their family members in northeastern Syria.

“ISIS could become operational overnight,” the official said, using the Arabic term for Islamic State. He added: “Two thousand prisoners can escape and become part of an operational force, and this is the operational goal of ISIS at the present time.”

This fear was reinforced by an analysis published on Monday by the Conflict Armament Research Group on weapons found following attacks by militants in the country's northeast, which concluded that the group may be more resilient than previously thought.

“ISIS still has a centralized and coordinated acquisition and distribution network in northeastern Syria, which is surprising due to the extent of unified efforts between local security forces and the US presence, and the ongoing monitoring and surveillance of alleged ISIS members,” he said. Devin Morrow, regional operations chief for Conflict Armament Research and lead author of the report.

Officials and experts say the US mission in Syria remains narrowly focused on counterterrorism, a policy shaped by past failures. The withdrawal of US forces from Iraq in 2011, when Biden was vice president, coupled with ineffective local governance, left a vacuum in which ISIS eventually flourished.

“Look at Biden’s position then, where we had to keep small teams there as a way to keep the boot under Al Qaeda in Iraq,” said Aaron Stein, author of “The US War Against ISIS.” Which chronicled the development of that mission.

“He believed that the withdrawal from Iraq in 2011, the way it was done, was a big mistake, and that has been the motivation behind the mission ever since,” Stein said.

But the question of how to get out cannot be answered through military means alone, experts say and officials acknowledge. “People say they can't be completely eliminated, and you can't really determine the endgame for the counter-ISIS mission. This may all be true,” said Khalifa of the International Crisis Group.

“But it's also political […] The Turks must be on board, the SDF must be on board, and the Russians and the regime must be on board.

“All of this is difficult, but it is not impossible,” she said. “It's very difficult because complex lifting requires investment and a lot of things that the United States doesn't do.”