“Yes, yes, come in, Nam Dong,” came the reply.

“Request a flare ship and an air strike. …We are under heavy mortar fire.”

The base was surrounded. North Vietnamese soldiers and allied insurgents, known to American forces as the Viet Cong or VC, approached through the jungle.

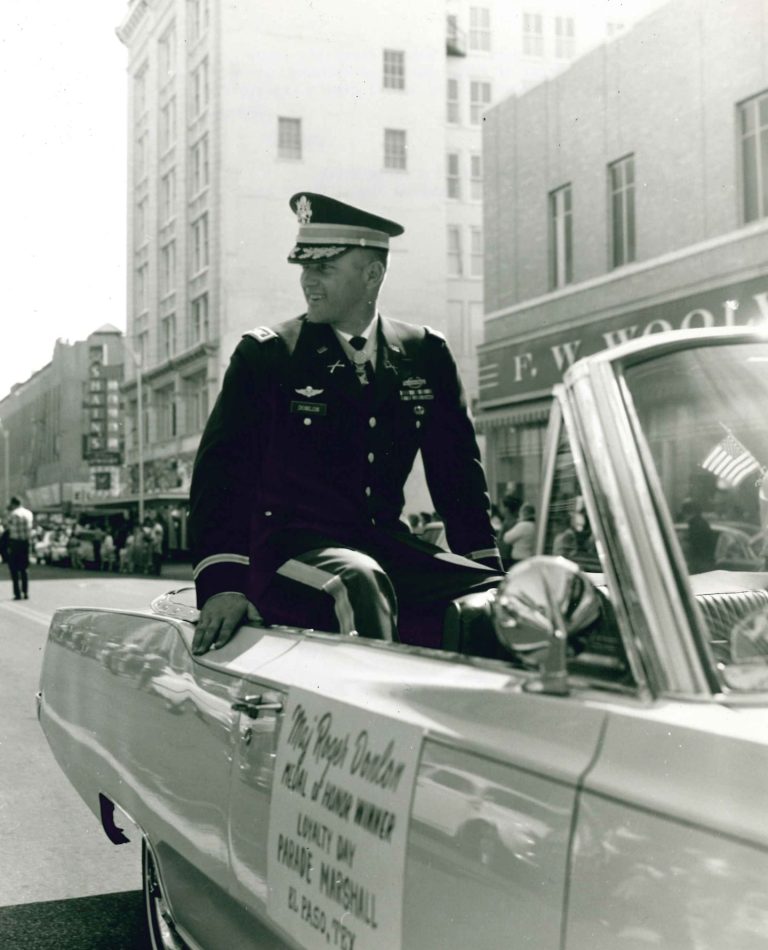

“The burning mess hall cast a strange dancing light over the camp, now dazzling with the swirling smoke and flashes of exploding shells. “It was mortar shells,” recalled Capt. Donlon, who was wounded four times during the battle and became the first Medal of Honor recipient of the Vietnam War for his defense of Nam Dong. VC is targeting us.” He died on January 25 in Leavenworth, Kansas, at the age of 89, more than 35 years after retiring from the Army as a colonel.

Days before the July 6, 1964, attack, expectations were growing that the North Vietnamese would attempt to overrun the camp – defended by more than 300 South Vietnamese soldiers, local militiamen, an American contingent and an Australian military adviser. Captain Donlon recalls that nearby Vietnamese villagers became nervous, possibly picking up clues to North Vietnamese plans.

The camp was not a large military outpost, but its location in a valley near Laos provided a crucial vantage point for monitoring and disrupting the movements of North Vietnamese insurgents.

Captain Donlon was checking the list of guards when the first attack wave hit. A shell hit the wall. The command center quickly caught fire. Captain Donlon and Master Sgt. Gabriel Ralph Alamo raced inside to salvage as much ammunition and weapons as possible.

A few yards away, a Vietnamese translator was struck by an explosion. His legs were blown off just below the knees. “He was dead within 30 seconds,” Captain Donlon wrote in his 1965 book, “Freedom’s Outpost,” co-authored with journalist Warren Rogers.

Two Viet Cong battalions—totaling at least 800 fighters—moved forward. They reached the last line of defense in the camp. American helicopters tried to bring reinforcements but returned to Danang due to heavy gunfire.

“Light the main gate,” Captain Donlon shouted for a flare, he recounted. In the glare of light, he shot three North Vietnamese fighters, killing two and wounding the third with a grenade as he tried to reach the cover of high grass. Captain Donlon noted that he was also wounded. His left forearm was bleeding. A piece of shrapnel caused a coin-sized wound in his abdomen.

“But nothing hurt too much, and my legs were fine,” he recalls.

Captain Donlon began crawling between the defensive pits dug in the camp to check on his team and the others. The Australian advisor, Officer Kevin Conway, was mortally wounded. Captain Donlon was wounded again. Shrapnel tore off his left leg. “For the first time, I felt real pain,” he recounted. “The commotion of the grenades was too much.”

A few minutes later, a mortar shell exploded a few meters away from Captain Donlon and another group. “I think I'm going to die,” he wrote. He lost consciousness and was lying halfway to the ammunition cache with wounds to his left shoulder and another to his abdomen. The Alamo is dead. So was another member of Captain Donlon's team, Sgt. john l. Houston.

Captain Donlon used strips from his shirt and one of his socks as bandages and a tourniquet. The North Vietnamese asked, via loudspeakers, the base to surrender or face invasion. Mortar shells continued to bombard the camp.

Finally, at dawn, he heard the sound of an approaching plane. Air raids bombed North Vietnamese positions. “Except for scattered small arms fire, the Battle of Nam Dong was over,” he recalls.

Among the dead were at least 57 South Vietnamese fighters, the Americans Conway, and more than 60 North Vietnamese attackers. Captain Donlon was awarded the Medal of Honor, the military's highest award for valor, by President Lyndon Johnson in December 1964. (There are currently 64 living Medal of Honor recipients.)

Roger Hugh Charles Donlon was born in Saugerties, New York, on January 30, 1934. His father worked in a coal and lumber yard. His mother was a housewife.

He left Air Force pilot training in 1955 after failing eye exams. He then stayed for two years at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, and withdrew for personal reasons, including the age difference with other cadets.

He joined the Army in 1958 and earned his Special Forces Green Beret at the U.S. Army Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina (now Fort Liberty).

During a second tour in Vietnam, he seriously injured his retina in 1972 while diving to the ground while under fire. He returned to the United States as anti-war marches and protests were nearing their peak. “Nobody likes to be on a team that doesn't have the support of the fans,” he told the Associated Press.

But he remained in the Army and served in leadership and training positions around the world including US Military Advisor to the Royal Thai Army and Battalion Commander with US Special Forces in Panama.

He earned his bachelor's degree from the University of Nebraska at Omaha in 1967 and his master's degree in government in 1983 from Campbell University in Boys Creek, North Carolina. He retired from military service in 1988.

Colonel Dolon's first marriage to Carol Chadwick ended in divorce. In 1965, he met a widow whose husband had been killed in the Vietnam War. Three years later, he married the former Norma Shino Irving, whose death has been confirmed. She said Colonel Donlon suffered from Parkinson's disease associated with exposure to defoliant Agent Orange.

Other survivors include a daughter from his first marriage; Three children from his second marriage. Six grandchildren. one granddaughter and two brothers. His son from his second marriage, Justin, died in 2022.

In 1998, Colonel Dolon published his memoirs, “Beyond Nam Dong.” He and his wife also worked with veterans groups including Wreaths Across America.

“The losses of war are not limited to the battlefield,” he said in a 2022 interview.