The United States added 2.7 million new jobs in 2023 as the economy defied a widely expected recession, but the monthly increases were exaggerated because of pandemic-era distortions in how they are calculated.

Make no mistake. The US job market is historically strong. Good workers are harder to find, and companies have to pay more to attract and retain them. The unemployment rate sits at a very low level of 3.7%.

However, official US employment reports have chronically overstated the number of jobs that will be created each month in 2023, potentially misleading Wall Street, the Federal Reserve and lawmakers in Washington about the true strength of the economy.

From January to October, the government initially overestimated job growth in nine of the 10 months. Ultimately, employment gains were reduced by 55,000 per month, an unusually large change.

Take last June as an extreme example. The government initially said 209,000 new jobs had been created before lowering its final estimate to 105,000 jobs two months later.

At the time, the stronger-than-expected report may have kept the Fed ready to continue raising interest rates amid concerns that a hot labor market was putting significant upward pressure on inflation.

What's going on?

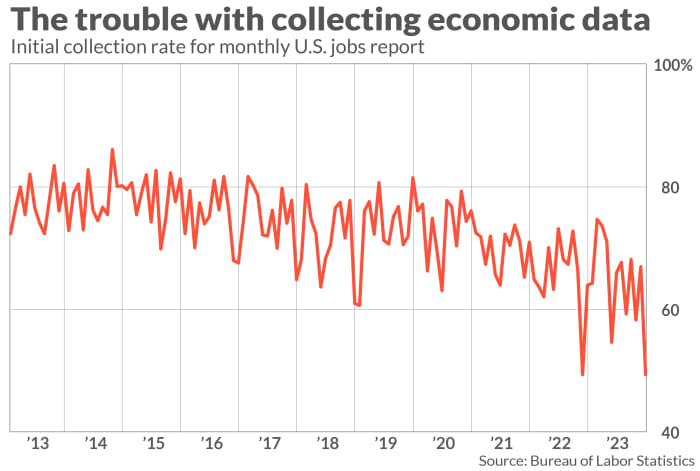

Some economists blame the low level of responsiveness of companies surveyed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics to determine the number of jobs created each month.

“Low response rates to the BLS monthly survey have been a problem since the beginning of the pandemic and continue to reduce the reliability of the initial estimate of job growth in any given month,” emphasized Richard Moody, chief economist at Regis Financial.

Take, for example, the December jobs report, when the government reported a larger-than-expected increase in new jobs of 216,000.

The so-called collection rate — the share of businesses that responded — matched a 32-year low of 49.4%.

By contrast, the average collection rate for the initial jobs report was about 73% before the pandemic.

The BLS says its own research shows no relationship between a low initial attainment rate and large changes between initial and final estimates of monthly job gains.

“Significant downward revisions in 2023 are not necessarily the result of a lower collection rate,” BLS economist Purva Desai said.

The agency said it is trying new approaches to try to get more companies to respond in a timely manner. The key is “just in time.”

In fact, most companies hand out their recruitment surveys eventually. The collection rate after the third and final estimate of the monthly jobs report is stable at 90% plus.

The big question is why so many respond so late.

Wiping fatigue is one reason. The pandemic also made it difficult for BLS to reach out to businesses to get them to sign up for the survey. Sometimes people at companies who respond to a survey work from home and don't respond as quickly.

Beyond that, no one seems to know.

“We also continue to advance efforts to increase initiation and attainment by offering respondents easier and more flexible ways to register and report their employment data,” Desai said.

Meanwhile, investors and policymakers should treat the initial jobs report and other economic reports with caution, Modi and other economists say. They all suffer from the same problem to varying degrees, making the quality of the data questionable at first glance.

“I will be watching to see how the 2024 estimates go,” Modi said.