New data confirms that last year was the hottest on record, while scientists warn that 2024 could be worse.

The European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service confirmed today that 2023 was indeed the warmest year since 1850 – a trend It is widely expected before the year is out Because it was too hot.

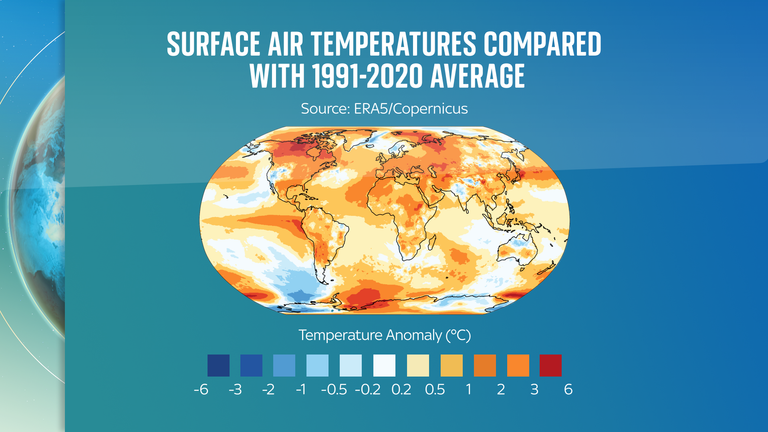

The average global air surface temperature in 2023 was 14.98 degrees Celsius, beating the previous record set in 2016 “by a significant margin” of 0.17 degrees Celsius.

Copernicus found that 2023 was on average 1.48 degrees Celsius warmer than levels before the industrial era, when humans began burning fossil fuels on a large scale.

Carlo Bontempo, director of Copernicus, described it as “a dramatic testament to how far we are now from the climate in which our civilization developed.”

But Met Office scientists believe this record could be broken again very soon, as their forecasts suggest 2024 could be even hotter, bringing more of the extreme weather experienced last year.

Copernicus said it was “likely” that the 12-month period ending in January or February this year would exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Last year's record-breaking record is a sign that the world is slowly closing in on reaching 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming — the level that countries agreed to target under the Paris Agreement, beyond which point adapting to climate impacts becomes more difficult.

Previous reports have already blamed rising temperatures for worsening wildfires in eastern Canada, drought in the Horn of Africa, and heavy rains and heatwaves in the United Kingdom.

Professor Piers Forster, interim chair of the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) and chief material officer, said that for the UK, “flooding from extreme storm intensity is the main impact from high temperatures of concern”. Climate change Mr.

He added that the country “is not immune to the most serious impacts around the world, especially those affecting food supplies, migration, conflicts, energy security and trade.”

“We cannot allow these impacts to become the new normal, nor do we have to,” he added.

Professor Forster added that we can also limit future temperature rises by “acting urgently to reduce emissions”.

He said reducing coal use and reducing methane emissions from fossil fuels and agriculture could cut the rate of global warming in half.

Why was 2023 so hot?

Professor Richard Bates of the Met Office said humans were rapidly warming the planet “through the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation”.

Last year also saw a warming shift The weather pattern is called El NinoWhen heat is released from the ocean, especially the tropical central-eastern region of the Pacific Ocean, into the atmosphere.

His colleague Dr Nick Dunstone said: “We expect a strong El Niño in the Pacific to influence global temperature until 2024. That's why we expect 2024 to be another record year, with the possibility of temporarily exceeding 1.5°C globally.” First time.”

Last year was record warm in the oceans and polar regions as well.

Copernicus said Antarctic sea ice reached record levels for this time of year in eight of the 12 months, while global average sea surface temperatures reached record levels for this time of year from April until the end of the year.

“Good news”, solutions and warnings

Climate scientists said acting quickly would help limit further temperature rise.

Dr Frederick Otto, senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London, said: “Every tenth of a degree counts.

“Even if we end up at 1.6°C instead [of 1.5C]It would be much better than giving up and not trying, and It ends up near 3C, which is where current policies will lead us“.

Professor John Marsham, an expert in atmospheric sciences at the University of Leeds, said: “We urgently need to quickly reduce the use of fossil fuels and reach net zero to maintain the liveable climate on which we all depend.

“The good news is not only that the public supports more climate action, it is often a win-win, for example, renewables in the UK are cheap and improve energy security.”

Ed Hawkins, professor of climate science at the University of Reading, said: “The devastating extreme weather events of 2023 are a warning that such events will continue to get worse until we transition away from fossil fuels and reach net zero emissions.”

He added: “It is a warning that we will continue to suffer the consequences of our inaction today for generations. It is a warning that we will regret not acting sooner when the technologies needed to reduce emissions are readily available.”